With global warming rapidly altering human life and the environment in the Arctic and with tense relations between Russia and the West threatening to derail a history of cooperation between nations bordering the Arctic Ocean, the United States is assuming leadership of the most influential intergovernmental group in the region—the Arctic Council.

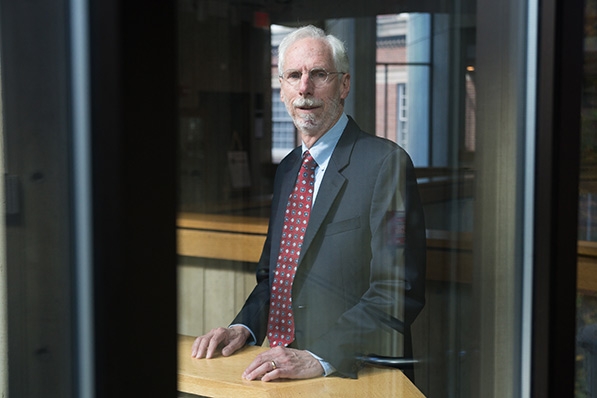

Research by Professor Ross Virginia in polar ecosystem ecology and policy issues has put Dartmouth at the convergence of historic challenges that will be addressed under U.S. leadership of the Arctic Council. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

On April 24 in Iqaluit, in the far northern Canadian province of Nunavut, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry will assume the chairmanship of the Council and open a discussion of the U.S. agenda for the next to two years with the Council’s eight permanent members: the United States, Canada, Denmark (including Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Russia.

Contributing to the U.S. chairmanship program is Professor Ross Virginia, whose work in polar ecosystem ecology and policy issues has put Dartmouth at the convergence of historic challenges that will be addressed under U.S. leadership of the Arctic Council. Virginia is the Myers Family Professor of Environmental Science, a professor of environmental studies, and director of the Institute of Arctic Studies within the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding.

In a recently co-authored editorial in The National Interest and in a published report following meetings with Arctic experts and governmental and NGO representatives, Virginia and his colleagues detail a number of issues the Arctic Council should address, from loss of sea ice and an increase in black carbon contamination to ratification of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea(UNCLOS) and sustainable economic development.

Virginia and his colleagues agreed that the Arctic Council and UNCLOS continue to be the primary mechanisms to ensure cooperation, engagement and transparency in the Arctic. The U.S. chairmanship program has set priorities in the following areas: Arctic Ocean safety, security and stewardship; economic and living conditions; and the impact of climate change.

“According to our report, cooperation can be maintained providing all Arctic countries continue to address Arctic issues on their own merits and manage competing national interests within a framework of international cooperation that has shielded this region since the end of the Cold War,” says Virginia. “The task of the United States will be to provide the leadership and political vision to keep the Arctic Council and the Arctic on a positive path. The United States must make clear that it is prepared to continue Arctic cooperation and welcomes constructive Russian activity in the region.”

Virginia, co-lead scholar of the State Department’s Fulbright Arctic Initiative, and Michael Sfraga, vice chancellor of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, lead a program of 17 scholars from the Arctic Council nations in collaborative projects that focus broadly on the impact of climate change. Their work will address research questions as well as solutions to issues ranging from global health and urban planning to biology, geology, law, and art.

The new report co-authored by Virginia resulted from meetings at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, D.C., in 2014 and 2015 under the auspices of the Institute for Arctic Policy (IAP), co-chaired by Dartmouth and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Virginia is the Dartmouth co-director of IAP, an institute of the University of the Arctic that since 2008 has convened meetings of international experts to report on critical Arctic issues.