A war hero, a senator, and a two-time contender for the presidency who criticized the current administration but never wavered in his loyalty to the Republican Party and to his country, John McCain, who died Saturday, is being remembered across the world for his integrity, his candor, and his patriotism.

In the Dartmouth community, his many admirers include some who met him when he visited campus during his presidential primary campaigns, and some whose memories come from other times and other places. Sharing their memories here are Linda Fowler, former director of the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy and the Frank J. Reagan Chair in Policy Studies, Emerita; Dirk Vandewalle, an associate professor of government; James Wright, former president of the College; and Justin Anderson, vice president for communications.

An Enduring Legacy and a Guide for the Future

John McCain built a special relationship with New Hampshire and with Dartmouth students during his 2000 presidential primary campaign. Making more than a hundred visits to the state in his campaign bus, the Straight-Talk Express, he won the primary by engaging voters, especially independents and moderate Republicans, in conversation about the direction of the nation.

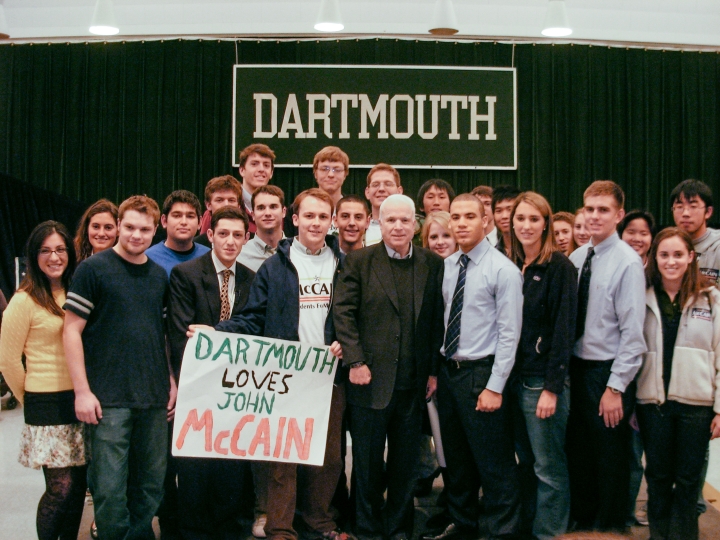

McCain drew energetic crowds to his events on the Dartmouth campus where students admired his self-deprecating humor, his accessibility to the press, and his candor about his policy positions. People in the audience would turn to each other and exclaim: “I can’t believe he just said that.” He came across as real at a time when politics was becoming more polarized and candidates were increasingly marketed by professional brand managers.

Although McCain lost his 2000 bid for the Republican nomination to George W. Bush and his 2008 race to Barack Obama, his campaigns still resonate with many New Hampshire voters. One January 2000 event in Alumni Hall stands out for its raucous, joyful embrace of McCain and his wife, Cindy. That memory invokes a time when Republicans courted student support, when conservatives looked forward, and when crowds expressed enthusiasm rather than anger. Whether a Democrat or a Republican, one appreciated the quality of the man’s character and his love of the United States.

John McCain is no longer with us, but his legacy of openness, integrity, and true patriotism remains as a guide to a more constructive politics for the future.

—Professor Linda Fowler

An Inspiration for a New Generation

I met John McCain when I was director of the Carter Center’s office for observing the Libyan elections in 2012. Sen. McCain came out to get a progress report on how events in Libya had unfolded since the 2011 revolution, and to take stock of what U.S. involvement had been.

At a time when long-held values in American politics are cavalierly being attacked, Sen. McCain always reminded us—no matter whether one agreed with his politics or not—of the value of honor, integrity, and honesty in the service of one’s country. One of the great men of American politics has left, hopefully inspiring a new generation to take up his ideas and battles.

—Associate Professor Dirk Vandewalle

‘A True Hero’

While I was at a few campus events when he spoke, I really only had one personal interaction with Sen. John McCain.

In the fall of 1999, when Sen. McCain was running his energetic “Straight Talk” campaign in New Hampshire, he sat behind me at a Dartmouth football game at Memorial Field. We chatted briefly—I think he was there for a quarter, perhaps. He had a pretty good briefing; he knew that I had served in the Marines and he knew something about the Dartmouth football team and our tradition. I found him very impressive. He was a true hero.

—President Emeritus James Wright

Riding the Straight Talk Express

In the fall of 1999, when I was assigned by ABC News to cover the presidential campaign of John McCain, I had no idea how fortunate I was. The other young wannabe political reporters at ABC were vying for sexier assignments. George W. Bush, Al Gore, and Bill Bradley were the plums. Even “outsider” Steve Forbes (remember him?) was more interesting than an aging white senator who had yet to crack the low single digits in any poll. Despite a long tenure in Congress, at the time McCain was distinguished more by scandal (as a member of “The Keating 5”) than by accomplishment.

No matter. I was thrilled to be one of the proverbial “boys on the bus” and not concerned that the trip might be short-lived. What I—and everyone else—failed to appreciate was that this particular bus—the Straight Talk Express—was destined for a long if ultimately unsuccessful ride.

Or was it? Was John McCain’s failed run for the 2000 Republican nomination unsuccessful? After his huge upset victory in the New Hampshire primary—with several stops at Dartmouth along the way—he set the agenda for the campaign. His maverick image and reform-minded message forced George Bush to modify his presentation and platform. The “compassionate conservative” from Texas became the “reformer with results.” McCain’s long resume stood in stark contrast to the inexperienced, late blooming, one-time wild child son of a former president. McCain offered himself as a “steady hand on the tiller” as compared to an unproven governor.

And then there was the military service. After being shot down on a bombing mission in Vietnam in October 1967, John McCain was a prisoner of war for five years in the notorious “Hanoi Hilton,” where he was brutally tortured while George Bush did his time on weekends as a member of the Air National Guard.

McCain was a patriot, a war hero, and a proven leader. He was a maverick unafraid to take on the establishment. Ultimately, that establishment—the money, endorsements, institutional support—and a bruising South Carolina primary were too much for McCain’s quixotic campaign. Bush prevailed and went on to defeat Al Gore after the Florida recount and become president. And I had a ringside seat for all of it. I learned how to be a reporter as I rode that bus—and later a plane—as we in the traveling press fired questions at McCain that he never ducked and always answered.

McCain returned to the Senate as one of its most powerful members. He used the bully pulpit and the continued media attention to advance causes he held dear and to launch his second, successful run for the Republican nomination. His comeback was ruined by a much younger upstart from the opposing party. Barack Obama’s historic candidacy was an unstoppable force McCain could not defeat.

A two-time loser, he could have retired to his beloved ranch in Arizona and lived out his years as a little seen and rarely heard from elder statesman of the Republican party. Instead McCain returned to the arena as a lion of the Senate. The decision to return to Congress was entirely consistent with the man. In the Senate, he would continue to pursue his lifelong credo: fighting for a cause greater than one’s self.

This is John McCain’s greatest gift to the country. The Straight Talk Express was the vehicle that propelled McCain—warts and all—to worldwide prominence. It gave him a platform to lead by example, to demonstrate what it means to serve over the course of a lifetime.

Back in ’99, when I took my seat on the nearly empty Straight Talk Express, I was ready for my assignment. What I wasn’t expecting, though, was to witness the ascension of an American original, a man who, because of his extraordinary life of service to his country and that wild, “unsuccessful” journey of the Straight Talk Express, will be accorded a State funeral later this week.

—Vice President for Communications Justin Anderson