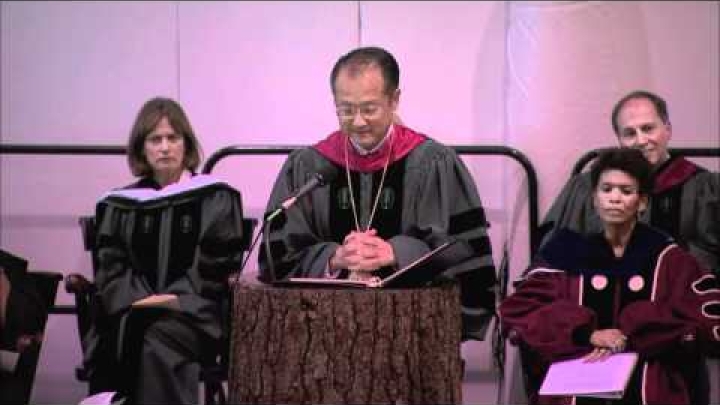

Dartmouth College Convocation, September 21, 2010 President Jim Yong Kim

Greetings students, faculty, members of the Board of Trustees, and staff. Thank you so much, Reverend Daughtry, for joining us.

We gather every year on this occasion to reflect on the legacy left almost two and a half centuries ago by the founders Eleazar Wheelock and Samson Occom, to seek knowledge, to educate the most promising students, and to prepare them for a lifetime of learning and responsible leadership. It is my great pleasure to welcome the class of 2014 to Dartmouth. You come to Hanover from 48 states and 43 countries, determined to learn, to be inspired, and to change the world. You are here because of what you have achieved and the promise of what you will accomplish.

Dartmouth will provide you with the tools you need to be transformative leaders in the global community. Take advantage of all this College has to offer, and you will no doubt be prepared, in the words of former Dartmouth president John Sloan Dickey, to take on the world’s troubles.

I also welcome the College’s new graduate students in the Arts and Sciences and those from Tuck, Thayer, and Dartmouth Medical School. In coming here you will soon learn how our strong community spirit enlivens the academic life of this great institution, promoting a remarkable level of collaboration and collegiality. At Dartmouth, you will have unparalleled access to faculty who are leaders in their respective fields. This is the formula that has made us so successful for so many years.

As our students enter their first year at Dartmouth, I enter my second. I am a sophomore, if you will, no longer new to this community, but not quite an upperclassman. I spent much of the past year doing what the members of the Class of 2014 will start in less than 24 hours: learning from Dartmouth’s outstanding faculty. I have been their student, as I will continue to be over the course of my tenure here.

Dartmouth’s faculty is comprised of teacher-scholars who are committed to instilling in you a passion for inquiry and analysis. They teach with the implicit understanding that you will join them in the discovery of new knowledge and engage in the student-faculty partnership that is central to our collective mission.

Among the many things I have learned from the Dartmouth faculty, one of the most significant lessons is that the ability to write clearly, effectively, and creatively may very well be the most important skill you will be taught in your time here. My expectation, as I have always said, is that each of you must go out and change the world after you have completed your time here. After many years of working on social problems like world poverty and lack of access to health care, it has become clear to me that for you to succeed in your world-changing mission you must leave Dartmouth with the ability to think clearly, imaginatively, and critically, and then render your thoughts in the written word.

There are over 1,800 undergraduate and graduate students entering the College this year. Many of you are published authors, even journalists and poets. Let me be the first to congratulate you for your successes. But let me also tell you that none of you has yet reached your potential in your ability to think critically and write effectively.

I made the mistake of not being properly introduced to the humanities and the lifelong task of becoming a better writer until graduate school, when I studied for my PhD in anthropology. It is not an exaggeration to say that studying new languages, philosophy, and literature as a graduate student fundamentally altered the course of my life. While I had always been interested in politics, the underlying assumption I brought into medical and graduate school was that science and technology were the keys to tackling the most important human problems. Now, don’t get me wrong: I am still a wildly enthusiastic believer in the power of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics to help us solve problems. But it was in graduate school that I realized changing the world would require the ability, as one of your professors put it to me just the other day, to “see the world as it is, imagine the world you want to create, and then render that vision in a way that convinces others that it is both attainable and desirable.”

Right now, you don’t know if it will be the study of literature, languages, or history that will help you see the world as it is. You don’t know if it will be the arts, philosophy, or mathematics that helps you imagine the world that you want to create. It’s hard work in all of these fields that will allow you to render your vision in a way that convinces others that it is both attainable and desirable. But let me warn you: this process will interrupt your life like it did mine. Don’t make the same mistake I did, of not engaging in this challenge until after you graduate. That’s the slow path to changing the world. Push yourself. Embrace the lifelong task of becoming a better thinker. Stoke your imagination, and learn to write more effectively every day.

In the midst of writing my own dissertation in anthropology, I had multiple episodes of writer’s block. So at that time, I began an exercise that some have called morning pages. I wrote three pages of handwritten text on anything that was in my mind as soon as I woke up in the morning. One of your professors gives this very assignment to all his students, and if you take his class, he will tell you that the text you create will be “the diary of the transformation of your inner lives.” To quote the journalist and author Brenda Ueland, if you want to write well, “Know that it is good to work. Work with love, and think of liking it when you do it. It is easy and interesting. It is a privilege. There is nothing hard about it but your anxious vanity and fear of failure.” Do not expect writing to be easy, but learn to love it. Embrace the possibility of failure as you expose yourself on the page. As Ueland says, if you want to write well, “Try to discover your true, honest, untheoretical self.”

The second lesson I have learned is that few traits are more important than persistence. In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell tells stories of great success and great failure, concluding that in addition to lucky breaks and accidents of history, what the most successful “outliers” have in common is persistence and around 10,000 hours to practice their craft.

As a child, I developed a deep appreciation for the importance of persistence, as it is something of a national obsession in Korea and among Korean Americans. There was an article in the New York Times a few weeks ago about a woman named Cha Sa-soon, who lives in Wanju, which is in South Korea, about 112 miles south of Seoul, the nation’s capital. Educated through only the fourth grade, Ms. Cha makes a living selling vegetables in the local market but has become famous in recent months for her persistence. Hoping to be able to drive her grandchildren to the zoo, she took her driver’s license test over 900 times in the last five years. Although she had to take three different buses and pay $5 each time she took the test, she finally received her license on the 960th attempt.

Now, if you find yourself in the city of Wanju for some reason—you may be on a foreign study or language program—you might want to stay off the road right around the time the zoos open. But you get my point. Persistence is one of the key habits of mind you will need to be successful here and for the rest of your life. And that’s not to say that you should decide now on one specific approach to your studies and stick with it regardless of the results. In 2002, psychologist Carol Dweck decided to study students enrolled in the fall semester of Columbia University’s general chemistry course, the equivalent of our Chem 5. Professor Dweck found that the majority of students could be placed into two categories: those with a fixed mindset, and those with what she called a growth mindset. As she explained in a 2009 speech, “‘Fixed’ mindset students believe their intelligence is just a fixed trait ... they worry about how clever they are ... they don’t want to take on challenges and make mistakes. The ‘growth’ mindset [students] think, ‘No, [academic success is] something that you can develop.’”

Professor Dweck found through her studies that students who exhibited the “growth” mindset received higher final grades than those in the “fixed” category. While many of the “growth” mindset students received bad results on one or two exams, the key difference between them and the “fixed” mindset students is that they were able to recover from a bad outcome. I maintain that your final grade in Chem 5 or almost any other class at Dartmouth is not an indication of your innate intelligence, but rather an indication of the quality of the strategy you choose.

The lesson here is that you shouldn’t be concerned about how you “stack up” against your classmates in terms of some notion of innate intelligence. We chose you because we know that all of you are capable of achieving great success here. Starting now, what matters most is persistence and a great strategy. There are many resources on campus—students, fellow classmates—to help you find the right strategy. You should begin finding those right now.

In my freshman year as a student at Dartmouth, I have also come to appreciate a third and final lesson: namely, the importance of community. To the new students here today, you will soon find yourself engaged in an atmosphere of collegiality and cooperation unmatched by any campus I know—an atmosphere you will likely not experience again after you leave these hallowed halls. Embrace it, and it will embrace you. Know that the people who supported you on your Dartmouth Outing Club trip and your first biology lab or in the sculpture studio are the ones who will be there supporting you in 2064 when the class of 2014 returns for its 50th reunion. Please learn from what I have learned. Develop as imaginers, thinkers, and writers. Be persistent. Be strategic. And fully embrace the entirety of the Dartmouth community.

Understand, as Malcolm Gladwell has written,

It is not the brightest who succeed. Nor is success simply the sum of the decisions and efforts we make on our own behalf. It is, rather, a gift. Outliers are those who have been given opportunities—and who have had the strength and presence of mind to seize them. The lesson here is very simple. But it is striking how often it is overlooked. We are so caught in the myths of the best and the brightest and the self-made that we think outliers spring naturally from the earth …

All of you here were offered admission to Dartmouth because we feel that you are precisely the kinds of future “outliers” that the world has been waiting for. You’re here at Dartmouth to learn, grow, and mature, so that once you leave us, you will go out into the world, make its troubles your own, and make those troubles melt away with your brilliance, your resolve, your compassion, and your tenacity.

We have been waiting all summer for you to arrive. We are so happy to have you here. And it is my great privilege to welcome each and every one of you to the 241st year of Dartmouth College.

Thank you.