Assistant Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences Thalia Wheatley hypnotized award-winning actor Alan Alda as part of an experiment on free will the pair conducted while Alda was recently at Dartmouth to learn about Wheatley’s brain research. Their experiments may be included in an upcoming PBS special Alda is making called Brains on Trial.

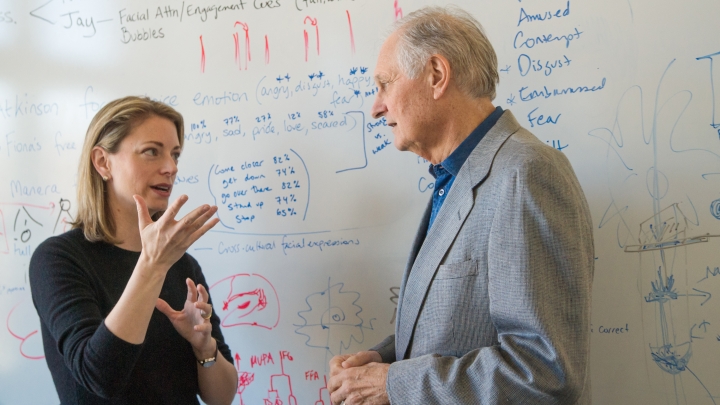

Professor Thalia Wheatley talks about her research with actor Alan Alda. Wheatley hypnotized the award-winning actor as part of an experiment on free will. The experiments, filmed in Wheatley’s lab during Alda’s visit, may be included in his upcoming PBS special “Brains on Trial.” (photo by Eli Burak ’00)

Alda, who was on campus March 30 with a production crew, filmed segments with Wheatley in her lab.

“It was an amazing experience for me to meet Alan Alda and share our research at Dartmouth. I think most people know Alan as a famous actor and playwright, but he is also this incredible ambassador for science,” says Wheatley.

“His PBS documentaries span more than two decades and what makes them really engaging is that he allows the viewer to see his learning process as it happens,” adds Wheatley. “Nothing is scripted or learned in advance, so what you see are these real moments of confusion and skepticism and questioning, but also these moments in which he ‘gets it’ and makes interesting new connections, always with enthusiasm and humor. I can’t think of any other shows that better capture the real joy of science.”

Wheatley’s research focuses, in part, on free will and how an action may be determined by brain activity before a person is aware of wanting to act.

Alda, a longtime host of science shows on public television, including the long-running Scientific American Frontiers, is working on the two-part special tentatively set to air sometime next year or in early 2014.

In Wheatley’s lab, Alda filmed segments in which his brain activity was monitored while he occasionally flexed his finger at times of his choosing. His task was to judge when he first became aware of wanting to flex his finger. He did this by watching a clock with a rapidly rotating second hand and noting the location of the second hand when he first felt the desire to move.

His brain patterns replicated a provocative finding in neuroscience literature, which is that his conscious awareness of wanting to move came a full second after neural activity started increasing in his brain. The finding suggests that the decision to move is made by the brain prior to any conscious awareness of that decision, explains Wheatley.

In hypnotizing Alda, Wheatley gave Alda hypnotic suggestions that he was unable to do certain things, such as separate his clasped hands and bend his arm. While hypnotized, Wheatley also told Alda that after hypnosis he would scratch his nose whenever she said the words “free will.”

After bringing Alda out of the hypnotic state, Wheatley asked Alda whether he “still believed in free will.” Alda immediately brought his hand part way to his nose before catching himself doing so, and laughed.

Wheatley also hypnotized undergraduates Jacob Batchelor ’12 and L.J. Sconzo ’12 while Alda watched. The four then discussed the implications of being able to disassociate the feeling of will from intentional action. Wheatley says that such studies suggest that actions proceed independently of our feelings of will over them.

Wheatley’s research looks at how people understand and react to each other and how human brains have evolved to handle the mental computations that underlie this social intelligence.

“We investigate some of the processes that make humans infinitely fascinating,” she says.

Her work includes studying how brains recognize other minds, how accepting humans are of approximation and distortion, and how information is conveyed in music and movement.

Wheatley received her PhD from the University of Virginia and has been at Dartmouth since 2006.