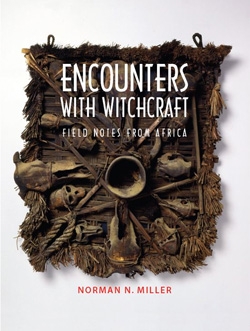

When the topic of witchcraft comes up most people think of the Salem Witch Trials of the late 1600s. But according to Norman Miller’s new book, Encounters with Witchcraft: Field Notes from Africa, witch-hunting and witchcraft-related crimes are found today in more than 70 developing countries.

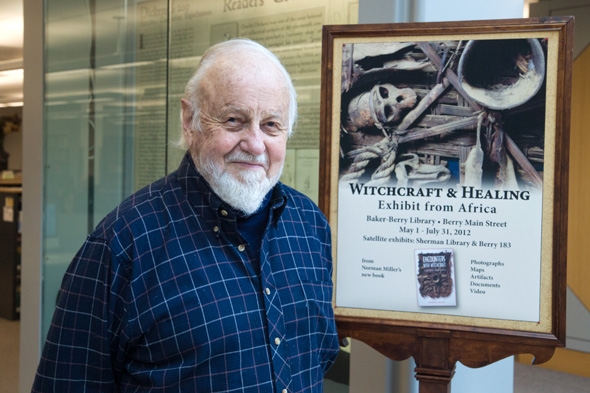

An exhibit entitled “African Witchcraft and Healing,” based on Norman Miller’s new book, is currently on display in Baker-Berry Library. Miller has taught at Dartmouth since 1980. (photo by Eli Burak ’00)

An adjunct professor in the Environmental Studies Program—who also holds a concurrent research professorship in the Geisel School of Medicine’s Department of Community and Family Medicine—Miller has lived intermittently in East Africa since 1960. The author of seven books, he spent six years writing his latest book, much of which he researched in rural Tanzania and Kenya.

An exhibit based on Miller’s book, entitled “African Witchcraft and Healing” opened recently on Berry Main Street in Baker-Berry Library. It includes 70 photos, maps, documents, art objects, and a video made by African students for the exhibit. Miller will give a gallery talk on the exhibit in the Current Periodicals Room of Baker-Berry Library on May 10 from 4 p.m. to 5 p.m. A book signing will follow in the main concourse. Miller will also deliver an ILEAD lecture, “African Witchcraft: An international Health Dilemma,” on May 17 from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m., in Silsby Hall, room 28.

Professor Miller spent six years writing his latest book, Encounters with Witchcraft: Field Notes from Africa, much of which he researched in rural Tanzania and Kenya.

Below is an edited interview that Dartmouth Now recently conducted with Miller.

How did you first become interested in researching witchcraft?

My book recounts this moment as I stepped off a grimy freighter in Mombasa, Kenya in 1960 and read a newspaper headline of an attack on a young British geologist in Tanzania. While prospecting for minerals he had mistakenly dug into a burial ground and was accused of being a witch. I realized then that witchcraft was an important but poorly understood reality. I had run into witchcraft stories in India and Thailand and I was alert to the topic. I started a “file,” mainly clippings from local papers, and wrote on the topic later in graduate school. And I wrote my first articles on the topic as a correspondent in East Africa. When I went back to Africa for field work, it was one of the village topics I collected data upon. The tragic life of Mohammadi Lupanda, the woman in my book who is tried and banished as a witch, focused my interest even more.

Why do you think witchcraft persists in Africa?

Several reasons. Witchcraft is a system of thought, a way of explaining unexplainable events such as death. It is a part of a heritage of beliefs. But the core reason that witchcraft persists is that it is profitable and politically useful. The key people who profit are the millions of indigenous or traditional healers who first, diagnose witchcraft as a malady, then sell the patient herbs, drugs, or medicines to cure and protect them from further witchcraft. Market women—including herbalists, healers, midwives, marketeers—make profits selling a wide range of herbs, drugs, amulets, and protective devices as curative and protective items. Witchcraft is also part of the belief system behind the killings for body parts that has plagued albino and elderly populations. The idea of sympathetic magic is at work here, the “sticking of pins in a doll” notion, that if you make medicines out of human body parts it will somehow have extraordinary power. The shock effect is important.

Those who claim the powers of witchcraft—Idi Amin, for example from the book—use these claims for political intimidation, power, and control. Elections in East Africa have been negated when the courts found a candidate used witchcraft threats against an opponent or to sway an audience. For some areas, witchcraft is a soto governo, a mafia-like under-government that serves as the local legal system, far from the national laws and in places where the government has little sway. This is gradually changing, but there are vast areas in each of these countries that are far from police posts, and far from the reach of government authorities. In the last 50 years I have seen a lot of villages “exit” from the national orbit; that is, return to basic subsistence economies for periods of time, refuse to pay taxes, refuse to cooperate with government schemes and in effect return to belief systems, including witchcraft, that provide answers.

You’ve said that witchcraft is a human rights issue. Will you explain this further?

Witchcraft beliefs lead to a form of scapegoating, of blaming others for unexplained events. Western psychologists suggest it may be a universal trend to some degree, called attribution. The unexplained sudden death of a child is a classic case. A tragic road accident, and the loss of crops or animals are others. When these events occur, the reaction is to search for the perpetrator, the one “who caused this.” Both individual and group (mob) action can follow. The accused is brought to some local trial or public accusation. Defamation as a witch, persecution, banishment, wounding, assault, or a killing can follow. The attacks are often by vigilante groups who believe they have the support of the village or neighborhood.

Collectively, this is a “human rights” issue. The United Nations has pointed to such cases as fundamental problems. African leaders speak against witchcraft violence, and Africans across the continent detest witchcraft violence. Specifically, when do witchcraft incidents become human rights issues?

- When evangelical churches use witch-hunting as a way to recruit, exorcise, and convert “witches,” sometimes violently.

- When children by the thousands in Central Africa are beaten and forced from their homes and into the streets and accused of witchcraft.

- When thousands of elderly women in western Tanzania are murdered as witches between 1999 and 2002.

- When “witchcraft villages” for women must be established in Ghana, South Africa, Tanzania, and elsewhere for the protection of women (and some men) who are accused of witchcraft.

- When refugee camps in several parts of Africa are plagued by witchcraft-based violence between refugees and internally displaced people who come from different cultures and cannot get along with each other.

Do you foresee any change in the future?

I believe witchcraft beliefs, at least those that lead to violence and extreme exploitation, will gradually fade. A lot depends on the education initiatives in village-level schools, secondary schools, and whether the universities begin to tackle the problem with courses like “Science vs. Witchcraft,” a course proposed at Makerere University in Uganda. One of the founders of anthropology, Bronislaw Malinowski, was prophetic on the subject as far back as 1943. He argued that with improved nourishment, better housing, preventative medicine, and adequate medical care, even the true believers will gradually change.

I have a hunch that if African leaders can take the witchcraft dilemma out of the courts, out of the hands of evangelical church people, and begin to see the violence and intimidation as “public health” issues, the mitigation of the human rights violence will gain traction.