By Lee McDavid

Rapidly changing health conditions in the Arctic, due in part to climate change and globalization, call for a dramatically new approach to research and delivery of services to improve the health and wellness in Arctic communities, according to a report released by the Dickey Center for International Understanding and the UArctic Institute for Applied Circumpolar Policy (IACP).

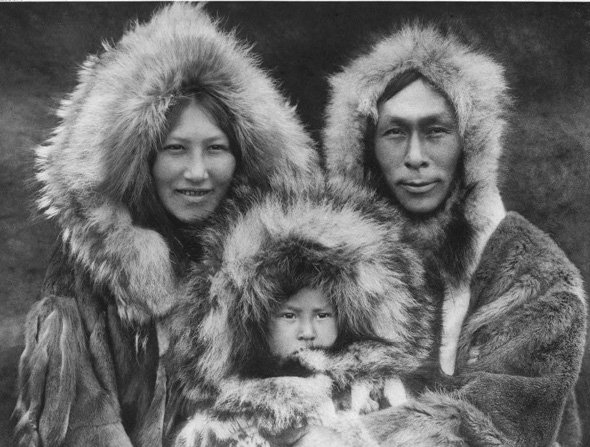

Since the time of this 1928 Noatak Inuit family picture, the Arctic has undergone radical shifts in the environment, as well as changing health and wellness needs. “The climate and ecosystems of the Arctic are changing rapidly and we can see real impacts on the health of people and their communities. Knowing how to respond is difficult,” says Ross Virginia, director of the Institute of Arctic Studies at the Dickey Center.” (Courtesy of Northwestern University Library)

Communities from the Canadian North to the Russian Arctic face a variety of health challenges ranging from the movement north of insect and water borne diseases as temperatures rise, the threat of environmental contaminants such as mercury, an increase in heart disease and obesity with a shift away from traditional foods, as well as the difficulty of providing health services to remote areas.

Twenty-seven health experts met last year at Dartmouth to tackle the critical health issues facing Arctic communities and to recommend ways of combating these problems. They conclude that a focus on wellness and the resilience of Northern communities is a more productive path to solutions than many traditional health care approaches.

“The climate and ecosystems of the Arctic are changing rapidly and we can see real impacts on the health of people and their communities. Knowing how to respond is difficult,” said Ross Virginia, director of the Institute of Arctic Studies at the Dickey Center.” The Dartmouth conference assembled an expert group from many Arctic nations to collect the latest ideas and build what we have called a new paradigm, or framework, to help health experts, communities, and policymakers focus on the most critical issues.”

The report’s recommendations include assuring that health research creates tangible benefits for communities as well as individuals, brings local and traditional knowledge into health practices, actively involves the community in making health research priorities, and focuses more on holistic practices that protect and sustain people rather than solely on health problems.

“The Institute for Applied Circumpolar Policy is playing a key role in fostering inter-disciplinary dialog on pressing social, economic, and security issues in the north,” asserted Kenneth S. Yalowitz, who at the time of the conference was director of the Dickey Center and co-chaired IACP with Mike Sfraga at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “This report calls for a new paradigm in Arctic health issues that is provocative and timely.”

The report, co-edited by Virginia and Yalowitz, will be distributed by the University of the Arctic during upcoming meetings of the Standing Committee of Arctic Parliamentarians in Nuuk, Greenland, in June.

The meeting on Arctic health issues that took place at Dartmouth from May 23 to 25, 2011, was the fourth in an ongoing series sponsored by the University of the Arctic’s Institute for Applied Circumpolar Policy, a collaboration between Dartmouth, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the University of the Arctic. The complete report is available online at the Institute for Applied Circumpolar Policy (IACP) website.

For more information, contact Lee McDavid, arctic@dartmouth.edu