“Acid rain” conjures up nightmare scenarios of destruction from above, and indeed this environmental insult meant death for fish and trees throughout the Northeast. The term surged into prominence in 1974 with the publication of a paper in Science entitled “Acid Rain: A Serious Regional Environmental Problem.”

F. Herbert Bormann, Dartmouth and Yale ecologist, 1922-2012, died on June 7. Bormann discovered acid rain in the Northeast and successfully lobbied Congress to take remedial action. (photo courtesy of Yale University)

Authors F. Herbert Bormann and Gene E. Likens had been Dartmouth College professors, eventually moving on to Yale and Cornell respectively. They called attention to smokestack emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides from the combustion of fossil fuels, identifying these emissions as the source of this environmental crisis.

In the mid-1950s, Bormann, Likens, and their colleagues began stream monitoring near West Thornton, N.H., leading to the establishment of the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. It was their studies of water flow and quality in the context of the ecosystem that eventually led them to the damage being done by acid rain.

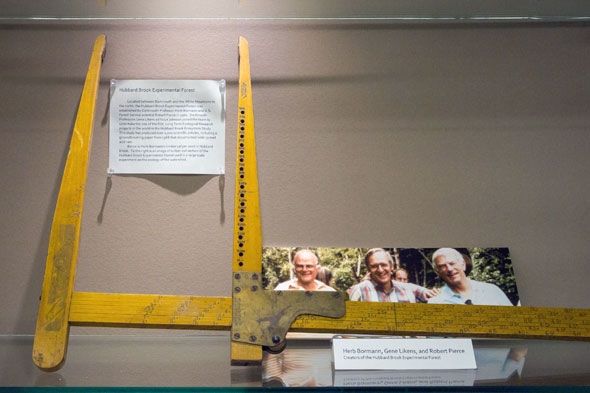

On display at the Class of 1978 Life Sciences Center are the giant timber calipers Herbert Bormann used in a large-scale ecological experiment at Hubbard Brook. In the small inset photograph are (from the left) Bormann, Gene Likens, and U.S. Forest Service scientist Robert Pierce, founders of the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. (photo by Eli Burak ’00)

In 1971, Bormann discovered the water was considerably more acidic than normal. Subsequent tests showed that the acidity of water all over the East Coast had increased up to 1,000 percent since the 1950s.

The recent death of Professor Bormann at age 90 on June 7 offers an opportunity to reflect on the legacy of his work, the fruits of which we all enjoy today.

“One cannot overstate the importance for science, society, and the connection between science and society, of the discovery of acid rain by Bormann, Gene Likens, and their colleagues,” says Matthew Ayres, Dartmouth professor of biological sciences. “Not only was the science itself powerful, but we can also admire the exemplary manner in which they brought this research to the attention of policymakers and the public—all over the world.”

Acid rain became a rallying point for environmental activists and a catalyst for governmental environmental action. Bormann testified at Congressional hearings that led to the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1990.

By 2003, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reported that sulfur dioxide emissions from power plants were down 41 percent from 1980 levels and nitrogen oxide emissions showed a 33 percent decline from 1990.

“Acid deposition has been substantially reduced, particularly in the Northeast, allowing lakes and streams to begin recovering from decades of harm from acid rain,” the 2003 EPA report states. “The ability of some lakes and streams to buffer acid deposition is improving in the Northeast, including the Adirondacks, a sign that recovery has begun.”

“Herbert Bormann clearly had a major influence on the field of ecosystem ecology, initiating and co-leading a major ecosystem study at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, developing an experimental approach to the study of whole ecosystems, co-discovering acid rain and its impacts, and much more,” says Richard T. Holmes, the Ronald and Deborah Harris Professor of Environmental Biology Emeritus.

“He advised and had a major influence on many students who have subsequently become leaders in the field of ecology. Bormann’s legacy is consequently long and influential.”