Dartmouth will host the “Pressure of Light Symposium” October 5 and 6, celebrating the designation of Wilder Physical Laboratory, where the first accurate measurements of the radiation pressure of light took place, as an American Physical Society Historic Site.

“The Nichols-Hull pressure of light experiment of 1900 to 1903 is regarded as one of the most significant experiments of American physics of all time,” says Sam Werner ’59, Thayer ’61, a member of the physics and astronomy Alumni Advisory Board.

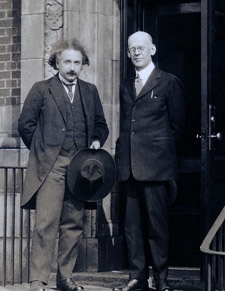

From 1900 to 1903, Dartmouth professors Ernest Fox Nichols and Gordon Ferrie Hull conducted the first precise measurements of the radiation pressure of light on a macroscopic body at Wilder Laboratory. While scientists had theorized that light might create a pressure, this was the first time that pressure had been accurately measured. The Nichols-Hull experiment is seen as a landmark discovery in radiative forces research, and continues to be influential.

In October 2011, Werner and Dartmouth professors Richard Kremer and Miles Blencowe wrote a letter to the American Physical Society Historic Sites Committee seeking Wilder’s designation as a historic site. The letter stated that the findings of Nichols and Hull are “clearly recognized as the starting point for all modern radiative force techniques in the manipulation of atoms and macroscopic bodies.”

The symposium features award-winning speakers, a reception, and the unveiling of a commemorative plaque on the front of the laboratory building.

“In addition to recognizing the landmark Nichols-Hull pressure of light experiment performed over a hundred years ago,” says Blencowe, chair of the department of physics and astronomy, “there will be an outstanding group of scientists presenting talks that show the relevance of the pressure of light for a range of cutting-edge science being carried out today.”

Over the past 15 years, scientists have used the principles of the Nichols-Hull experiment to cool down atoms close to absolute zero. These atoms are used in atomic clocks, on which GPS systems depend. Furthermore, scientists are now able to precisely select and manipulate cells, even DNA molecules, using radiative forces—a technique known as “optical tweezers.” The radiation pressure findings of Nichols and Hull were also applied in the development of hydrogen weapon technology. On a more basic level, their findings explain why the pressure of light forces comets’ tails to bend away from the sun.

The basic structure of Wilder Laboratory, where Nichols and Hull conducted their groundbreaking research, remains intact today. The logbooks from the Nichols-Hull experiment are kept in Rauner Library, while Nichols’ radiometer is kept at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. For his research, Nichols won a Rumford Prize in 1904, awarded by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Nichols left Hanover in 1903 to teach at Columbia University, before returning to Dartmouth as its president in 1909. During his tenure, Nichols increased Dartmouth’s endowment and attendance. Over his seven-year presidency, Nichols oversaw the first Winter Carnival and the start of the Dartmouth Outing Club, and established the Council of Alumni.

“The event also gives us the opportunity to recognize the remarkable achievements of Ernest Fox Nichols,” says Blencowe, “not only as a physicist, but as the 10th president of Dartmouth.”