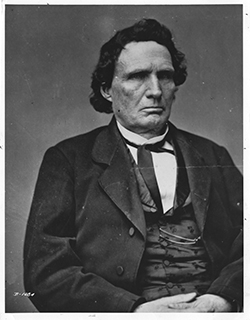

Thanks to a Harvard man, a son of Dartmouth is finally getting his due. The portrayal of U.S. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens (R-Pa.), Dartmouth Class of 1814, by Tommy Lee Jones, Harvard Class of 1969, in Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln is earning acclaim for the Oscar-winning actor. It is also raising awareness of the prominent role Stevens played in the passage of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery.

“Tommy Lee Jones did a great job, and it’s wonderful to have that kind of actor portraying him and getting the public’s attention,” says Beverly Wilson Palmer, editor of the Thaddeus Stevens papers at Pomona College. “Because of the strength of Jones’ performance, Thaddeus is not going to go away, and I won’t have to explain who he is anymore!”

As Spielberg’s movie showed, Stevens’ “position as chairman of the Ways and Means committee in the House is so important” in the passage of the 13th Amendment, says Dartmouth history Professor Robert Bonner. “It had already passed the Senate, but as the most powerful person in the House he had to do some heavy lifting. His role in the passage of the amendment is equal only to Lincoln’s.”

In addition to helping push through the ban on slavery, the Vermont-born lawyer and abolitionist also played a key role in the ratification of the 14th Amendment, which ensured citizenship for everyone born in the United States and “full and equal benefit of all laws.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Tony Kushner, who wrote the Lincoln screenplay, says of Stevens in a November interview on NPR’s Fresh Air show, “He was an absolutely astonishing human being, a great legislator, a moral visionary, and a moral giant, and a real radical in every sense of the word, in terms of his thinking about race and economics, really an astonishing guy, who I think has been woefully underappreciated.”

While Stevens was instrumental in advancing the great civil rights amendments to the U.S. Constitution, prior to Lincoln, he had perhaps been best remembered for leading a bitter drive to impeach President Andrew Johnson. The efforts of Stevens and the Radical Republicans to oust Johnson for violating the Tenure of Office Act ultimately failed, as the president was acquitted by a single vote in 1868. Additionally, Stevens was reviled in the South due to his wish to confiscate and redistribute southern land to freed slaves.

The negative portrait of Stevens was reinforced by the landmark 1915 film The Birth of a Nation. This controversial silent film depicted him as the villainous and amoral Austin Stoneman, hell bent on making the South pay in Reconstruction and also scandalously involved in a romantic relationship with his mulatto housekeeper Lydia Hamilton Smith. (Wilson Palmer and other historians say there is no evidence of a romantic relationship between Stevens and Hamilton Smith, contrary to a pivotal final scene in Lincoln.)

“The Birth of a Nation depiction of Stevens is absolutely horrid,” says Dartmouth associate history Professor Leslie Butler. “It’s cruel and even grotesque. His wig is utterly ridiculous and his clubfoot is kept constantly in view. The ‘deformed’ foot seems to almost become a symbol for (filmmaker) D.W. Griffith and Thomas Dixon, who first wrote the character in his novel The Clansman of Stoneman’s/Stevens’ supposed moral deformity.”

Another unflattering film portrayal came in Tennessee Johnson, the 1942 biographical movie about President Johnson, in which Stevens was played by Lionel Barrymore. While this film “downplays Stevens’ views on racial equality,” Butler says that like The Birth of a Nation, it also portrays him as “a vindictive fanatic whose approach to Reconstruction is tragic and doomed.”

Contrast these two portrayals to Lincoln, which shows Stevens to be “a moral visionary precisely because of his progressive views on racial equality,” says Butler. “He’s a bit hot-headed and rhetorically flamboyant, yes, but in an endearing way. And his racial egalitarianism clearly sounds the most like ‘us’ today, even though Lincoln and other Republican leaders needed him to soft-pedal it in Congress in 1865.

“That scene, when he speaks before congress in support of the (13th) amendment, did a nice job of showing just how progressive and visionary Stevens was, precisely because it demonstrated how radical his views were for his own era, which is an important reminder that historical reputation is a long-term phenomenon,” Butler says. “Sometimes a historical figure needs history to ‘catch up’ to remember him or her well, as happened in Stevens’ case.”

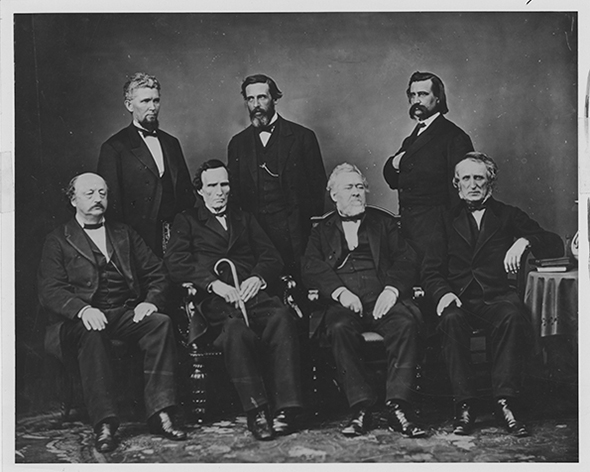

Images From the Life of Thaddeus Stevens

Dartmouth’s Rauner Special Collections Library has some of Stevens’ papers in its collection, a few of which are included in the Flickr set below. Beverly Wilson Palmer, who spent five years collecting and editing the Thaddeus Stevens papers, said he didn’t leave an extensive collection of personal papers. Among those in Dartmouth’s collections are notes for a speech he delivered in 1866 on voting rights, a personal letter of recommendation written on Ways and Means Committee stationery, and the speech Stevens delivered at his 1814 Dartmouth commencement (all students delivered commencement addresses in Dartmouth’s early days). Click through the Flickr photo set to see scans and explanations of these and other documents, as well as photographs and an engraving of Stevens from the collection of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College.