In a time flooded with media that’s available virtually anywhere, anytime, there is a vast world of moving images and sound recordings on the verge of extinction, says Film and Media Studies Professor Mark Williams.

Media records of our cultural history are threatened because their value is not understood, their provenance is unknown or their formats are obsolete, says Williams, head of Dartmouth’s Media Ecology Project, which is racing to identify and save these threatened resources.

Scholars, archivists, media technology developers, and other key players who see preserving and understanding this history as an urgent mission will convene at Dartmouth for a Media Ecology Project symposium Friday and Saturday. The Leslie Center for the Humanities provided funding for the event.

”This is a sustainability project—that’s the meaning of ‘ecology.’ These resources will dry up and blow away,“ Williams says.

And while images of antique celluloid movies moldering in storage may come to mind at the mention of moving image preservation, digital media can have a shorter half-life as technology evolves, he says. ”There are so many digital materials we can’t even read anymore.“

Through development of digital tools that give scholars and teachers access to media archives and collections, the Media Ecology Project can provide opportunities and motivate new scholarship that will ”create an environment of interest“ to keep resources such as boxes and boxes of 16 mm news film or quirky movie shorts from landing in the ash bin of history.

”We can step up as a scholarly community to provide better support for the essential work performed by the archives. This is about the sustainability of cultural memory,“ Williams says.

Symposium participants from The Library of Congress, The UCLA Film and Television Archive, The Orphans Film Symposium, The University of South Carolina MIRC Archive, the WGBH Archive, Critical Commons, and the Dartmouth Film Archive will provide the entries for the festival.

”There is nothing that archivists enjoy more than producing a screening event together,“ Williams says. ”It is a friendly competition, a ritual of their community. These people will pull some spectacular things from the collections.“

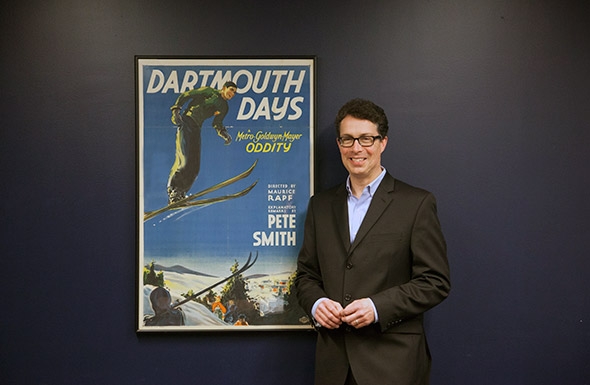

Dartmouth’s contribution to the festival will be Dartmouth Days (Rapf, 1934), directed by the godfather of film studies at Dartmouth, Maurice Rapf ’35, and Losey on Film (Fauer, 1971), a documentary made during the 1970 Dartmouth residency of filmmaker Joseph Losey ’29.

Dartmouth Days is a wise-cracky, quirky short about Dartmouth produced in 1934 by MGM and directed by then-student Rapf, whose father was an MGM mogul, Williams said. Rapf went on to a career as a screenwriter; he was founder of the Screen Writers Guild; and he helped establish film studies at Dartmouth, where he became a film studies professor.

Losey on Film documents classroom exchanges with Losey during his residency on campus intercut with clips from his acclaimed film Accident, a 1967 crime drama written by Harold Pinter.

”Losey on Film is a very smart piece of work," Williams says.

Support for the symposium was also provided by the Office of the Provost, The Dartmouth Library, the Dean of Arts and Humanities, The Neukom Institute, and the Department of Film and Media Studies.