Professor David Lagomarsino’s curiosity and genuine interest in people become clear as soon as you meet him.

Seated at a desk piled with copies of hand-written, 16th-century documents, under portraits of Spain’s King Philip II and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Lagomarsino turns an interview into a conversation that elicits his interviewer’s opinions and experience. This talent for engaging others is what makes Lagomarsino a great teacher, say students and alumni who have studied with him during his 39 years at Dartmouth.

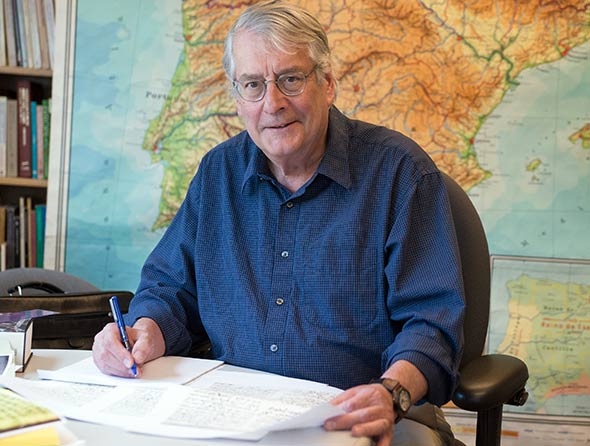

Years ago, after he’d been offered a job in publishing, Professor David Lagomarsino happened to see an advertisement about teaching Spanish history at Dartmouth. “It was the only job in the universe designed for someone who had studied everything I had just studied,” he says. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Most recently, the Class of 2013 chose Lagomarsino to receive the Jerome Goldstein Award for Distinguished Teaching. Established in 1978 by Jerome R. Goldstein ’54 and bestowed each year by a vote of the graduating class, the award recognizes “undergraduate teaching of the highest order.”

The honor is presented each year as part of Class Day celebrations over Commencementweekend. When Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Michael Mastanduno presented the award at the Old Pine Lectern this year, it was a hat trick for Lagomarsino. He’d already been selected for the Goldstein Award twice—by the Class of 1984 and then by the Class of 2005. In the 34 years since it was established, Lagomarsino is only the second professor to receive the Goldstein Award three times. The other is Professor Kenneth Shewmaker, a history department colleague who received the prize in 1986, 1996, and 2004. Shewmaker retired in 2008.

Colleen Carroll ’13 took several classes with Lagomarsino and worked with him as a Presidential Scholar research assistant. His teaching “possessed a miraculous storytelling quality,” she says, adding that “his investment in building relationships with students outside of the classroom was unmatched. Whether it was a lunch at the Canoe Club or an email with travel tips for seeing historical London, Professor Lagomarsino served as not only an outstanding professor but also a welcoming mentor.”

Joshua Kornberg ’13, a class valedictorian, calls Lagomarsino a “phenomenal” teacher and says his interest in his students as individuals is clear. “He always makes himself available outside of class for questions; he asks us about our interests and concerns and future plans; he provides detailed hand-written comments on our papers; he even follows us in our extracurricular pursuits—I used to receive emails from Professor Lagomarsino commenting on my articles in The Dartmouth. I’m very lucky to have learned from such an outstanding man.”

Professor David Lagomarsino addresses the crowd during the 2013 Class Day Exercises. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

There are similar stories from Dartmouth alumni. Lagomarsino remembers his very first student at Dartmouth. He says a somewhat bewildered first-year student by the name of Mark C. Hansen ’78 was led to his office by a senior colleague, Professor Leo Spitzer, in the fall of 1974—the first student to enroll in Lagomarsino’s first seminar class.

“I started with a freshman seminar and then took two more classes with David, followed by a thesis,” says Hansen. “He was and is a gifted teacher, a man of great erudition and learning who not only likes students but takes pains to help them develop as thinkers, writers, and people. He is truly a Dartmouth treasure, part of the unequalled undergraduate teaching tradition that drew my two daughters to Dartmouth.”

Hansen went on to endow, with his wife, Anne S. Hansen, the Charles Hansen Professorship in 2005. The chair, named for his father, acknowledges teaching and the advancement of liberal education. Dartmouth granted Lagomarsino the Charles Hansen Professorship in 2005.

“When we established the Hansen Professorship, I certainly hoped that he would be the first recipient,” Hansen says. “But it was all the more gratifying that the College made that decision, thereby recognizing what so many students have known for 39 years: David Lagomarsino represents the best of what Dartmouth has to offer its students.”

A Temporary Occupation

“I am only accidentally a historian,” Lagomarsino says. A traveling fellowship from Harvard took him to Cambridge in England, where he intended to work on a two-year master’s degree in history.

“I fell under the spell of my mentor at Cambridge, the great professor Sir John Elliott,” a leading historian of the early modern period in Europe, particularly 16th- and 17th-century Spain.

Elliott convinced Lagomarsino to work for a PhD, and to do it in three years. Lagomarsino made Philip II of Spain the focus of his work, and in the process discovered a knack for reading the impenetrable hand of Philip II, one of the first kings who conducted the business of the empire by personally penning his orders and annotating incoming reports—a boon to historians, Lagomarsino says.

Even with a new PhD, “I planned all along to go into business. History was a diversionary side trip,” Lagomarsino says.

He was considering a job offer in publishing in New York when he spied an ad about an academic position teaching Spanish history at Dartmouth. “It was the only job in the universe designed for someone who had studied everything I had just studied,” he says.

He took the job, moved to Hanover with his wife and 3-year-old son and started work. “The idea was to come here for four or five years. . . . Then I could go and get a real job. That was 39 years ago,” he says.

As he developed his classes, Lagomarsino’s passion for the drama and grand characters of the Golden Age of Spain inspired his students, and he discovered a shared enthusiasm and exchange of ideas with Dartmouth undergrads that inspired him all the more. He still hears from alumni in all fields—an insurance company president, a state Supreme Court justice, a business school dean—who recall classes with him and specific stories from the reign of Charles V or Philip II.

He teaches “The History of Europe in Medieval and Early Modern Times,” a survey course that emphasizes critical reading and interpreting sources through reading of primary documents like the Magna Carta and contemporary writings from the time of Charlemagne. He also teaches “Early Modern Europe” and “Spain and the Golden Age.”

But the class he enjoys most, he says, is a first-year seminar on the Spanish Armada. “That legendary battle takes place in 1588. The battle goes on over nine days but to understand what happens and why, you have to back up and understand the 50 years leading up to it and all the various personalities and the different political and ideological interests at play. That’s a challenge—but also enormous fun to teach.”

Maura Farley ’13, also a valedictorian, captures this sense of fun in a tribute to Lagomarsino.

“Emperor Charles V would be most proud of Professor Lagomarsino, for he sails far, far beyond the Pillars of Hercules in all of his endeavors as a historian and a teacher,” she says. “I know that I speak for many of my peers when I say that it was a true privilege and a true pleasure to work with this ilustrísimo y excelente señor!”