Generations of television viewers remember Alan Alda for his Emmy-winning performance as Hawkeye Pierce on the 1970s show M*A*S*H, for his role as a presidential candidate on The West Wing, and for playing Alec Baldwin’s father on 30 Rock.

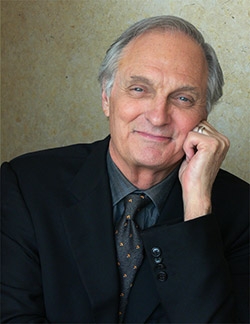

Alan Alda will deliver his Montgomery Endowment lecture, “Getting Beyond the Blind Date With Science,” at 4:30 p.m. on October 10. (Courtesy of Royce Carlton Incorporated)

But the scientific community knows him from PBS’s Scientific American Frontiers, which Alda hosted from 1993 to 2005.

Since 2009, the actor, director, and writer has also become known for helping scientists communicate their research through courses and workshops at Stony Brook University’s Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science. Alda, who last month was awarded the James T. Grady-James H. Stack Award for Interpreting Chemistry, sponsored by the American Chemical Society, will talk about these communication strategies and techniques October 10 and 11 when he visits Dartmouth as a Montgomery Fellow.

Alda will deliver his public Montgomery Endowment lecture, “Getting Beyond the Blind Date With Science,” at 4:30 p.m. October 10 in Moore Theater, with simulcast viewing in the Hood Auditorium. Admission is free but tickets are required for seating in Moore; they are available at the Hopkins Center box office.

The Montgomery Endowment, which invites inspiring individuals to the College to live, work, and share their perspectives, was established in 1977 through a gift of Kenneth ’25 and Harle Montgomery. Alda is the third Montgomery Fellow to visit Dartmouth during fall 2013. Filmmaker Werner Herzog was the first, and novelist, philosopher, and MacArthur “genius grant” winner Rebecca Newberger Goldstein is in residence at Dartmouth through the end of fall term.

During his Montgomery residency, Alda, a visiting professor in Stony Brook’s School of Journalism, will interact with more than 200 Dartmouth students. He will visit a biology class and a combined physics class, and meet with theater department students. He’ll also teach two master classes for graduate students and faculty members.

“It’s probably never been more important for the public to understand science,” says Alda in a video on the center’s website. “Communicating science with clarity can only help scientists make their work better understood by voters, by policymakers, by funders, even by researchers in other disciplines.”

Some of the Alda Center’s techniques have already been incorporated into Dartmouth classrooms.

Nancy Serrell, a former science journalist and the director of Science and Technology Outreach in the Office of the Provost, invited several faculty members to participate in a weekend science communication workshop at Stony Brook’s Long Island, N.Y., campus last fall. The group agreed that this approach—which incorporates improvisation exercises used by actors—might be a good fit for Dartmouth, and Serrell began looking for colleagues to create a new interdisciplinary science communication course for graduate students. The cross-listed graduate course, “Communicating Science,” was launched this term.

The course is a unique cross-department collaboration. Serrell and Mark McPeek, the David T. McLaughlin Distinguished Professor of Biological Sciences, have teamed up with Christian Kohn, a theater department lecturer who is currently appearing in the Northern Stage production of Twelve Angry Men in White River Junction, Vt., and Gifford Wong, a PhD candidate in Earth Sciences with a background in improvisational theater, to develop a Dartmouth version of the Stony Brook model.

In the new course, Kohn and Wong take students through improvisation exercises at the start of class, such as pretending to pass a ball around the room without using any verbal cues. Then, says McPeek, “Nancy and I take over and we talk about applying that to real scientists talking to various groups. For example, you can’t use the same visual aids at a public lecture that you would at a professional meeting. So how do you get the same information across in a way that’s understandable and appealing to people, and doesn’t put them to sleep?”

While Alda was on campus, it was announced that Dartmouth has entered into a partnership with Stony Brook University’s Alda Center.

“Dartmouth has agreed to collaborate and disseminate this model of teaching scientists, mathematicians, engineers, and clinicians to be more engaging and effective communicators,” says Serrell. “This partnership is the beginning of what we hope will be a broader partnership, including other institutions that would like to see this idea more widely disseminated.”

Dartmouth faculty members Thalia Wheatley of psychological and brain sciences, Robert Caldwell of physics and astronomy, and Brad Taylor of biological sciences—who participated in the weekend program with Serrell at Stony Brook—found it to be extremely beneficial. As Taylor, who teaches freshwater ecology to undergraduates and graduate students, points out, “Scientists aren’t traditionally taught to communicate science to everyone. And what Alan is aiming for is not to affect how we normally communicate, but to enable people to reach a broader audience so everyone is more scientifically literate.

During his visit to campus in April 2012, Alan Alda met with Professor Thalia Wheatley to discuss her research. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

“There were a lot of things I took away from it, such as using vivid imagery, which applies well to biology, from genes to ecosystems, as well as the importance of distilling your message and getting to what he called the ‘so what?’ Some of the language used by the various sciences is foreign to some people, but it is used for accurate and precise communication. Asking scientists to not use their language can be scary, because the precision and accuracy may be lost.”

Caldwell jokes that the various role-playing games and improvisational exercises they learned at Stony Brook didn’t involve “leotards and mimes,” but rather were designed “to help break down barriers and to get us to listen to and connect with another person.” This fall, Caldwell is teaching an advanced course on general relativity for undergraduates and graduate students, as well as a class for first-year graduate students on how to be a teaching assistant.

“When you stand in front of a classroom there are various invisible barriers between you and everyone else that wouldn’t be there if you were sitting over a coffee table,” he says. “Some of the exercises were to help us get over those barriers and to understand that you need to have empathy and sympathy for those who don’t know the jargon you do and who may be coming from a different mindset.”

Wheatley, who is teaching Psychology 1 and a class in research methods this fall, says she learned “the importance of connecting with the audience” and of “sharing moments of discovery” from her research with students in the classroom. “What he taught me is that to really engage, you’ve got to remind students that some of the deepest, biggest questions are being answered right now, or haven’t been answered and are waiting for them to become scientists and answer. Our brains are wired to engage with others, not to listen to a person reading off PowerPoint slides. Once you can connect with people and engage them, then the information gets absorbed—deep learning happens. It’s a richer way of teaching and communicating.”

Wheatley worked with Alda as a consultant on Brains on Trial With Alan Alda, which aired on PBS in September 2013. “His love of science really comes across when you see him in person,” she says. “He renews people’s love for science—what it means and why it’s interesting.

“He has a very simple message: ‘Here’s something beautiful that you’ve been missing,’ and then he unpacks it for people and awakens their joy of discovery about science. His genuine love of discovering something new is infectious.”