From the classroom to the lab and the library, Dartmouth faculty members embody an ethos that melds research and teaching, twin disciplines that Dartmouth believes are inseparable. “Education is more powerful than instruction,” says Nathaniel Dominy, associate professor of anthropology.

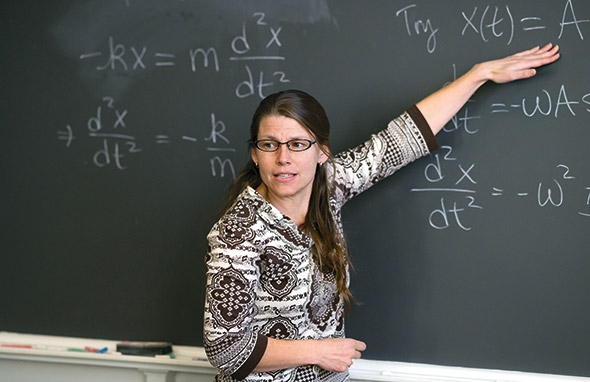

“There is a huge difference between learning what somebody else figured out and venturing into new territory where you don’t even know if you’ll find the answer,” says Associate Professor of Physics and Astronomy Robyn Millan. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

There is a deep truth that Dartmouth students encounter in the classroom as they work with active researchers: All there is to know isn’t set down in a textbook or outlined in a lecture—far from it. The world is still being discovered, and Dartmouth students see that in action. More often than not, they become part of the process of discovery.

“The questions we ask are a reflection of who we are,” says Robyn Millan, associate professor of physics and astronomy. “There is a huge difference between learning what somebody else figured out and venturing into new territory where you don’t even know if you’ll find the answer. The possibilities are endless, and we get to chart the course.” That’s just one reason it’s important for students to be exposed to research, she says.

This is true in arts and humanities just as much as in science, math, engineering, and technology. As Melanie Benson Taylor, associate professor of Native American studies, says, “For many of us who live and work in Dartmouth’s intellectual community, our next book is often born in the classroom, and our students are its first caretakers.”

Taylor’s current book project “emerged directly from the courses I teach. That’s a testament to the remarkable synergy of research and pedagogy fostered here,” she says.

Excelling at teaching and research simultaneously is deeply demanding. But, says Leslie Butler, associate professor of history, “I think it is as worthwhile as it is difficult. Teaching and scholarship are two sides of the same coin—and if you care about both, Dartmouth is truly an amazing place to be.”

Faculty find themselves impressed by the learning and growth that takes root here. It begins year one, and doesn’t end at Commencement. Associate Professor of MathematicsCraig Sutton cites a particularly “memorable and rewarding experience: watching my student Seunghee Ye ’10 defend his senior thesis. It was the culmination of nearly four years of formal and informal discussions, and a lot of work on his part. It was an amazing experience to realize in that moment how much he had grown as a mathematician since I met him in a linear algebra class during his first year.”

Millan tells of a former student (with both undergraduate and master’s degrees from Dartmouth) who “went to Antarctica with me last year to help launch our research balloons. It was a real thrill to work alongside him as a colleague and see how much he had learned and grown into a real leader. It is always so amazing to work with students and then watch them go off to jobs or graduate school and hear about all the amazing things they’re doing.”

The common theme in these stories is having a particular sort of impact on students: opening minds, enriching awareness of complexity, raising students’ willingness to ask questions and pursue new ways of thinking and doing.

“I am excited when I hear from them, sometimes years later, about the impact my course has had on them and how they view the world, when they feel like my course changed them as a person, for the better, and they see possibilities now that they hadn’t been aware of before,” says Associate Professor of Art History Mary Coffey.

Sonu Bedi, associate professor of government, puts it this way: “My constant hope is that my research will inform my passion and excitement for teaching. Teaching for me is getting students to think that they could be wrong. They may, of course, ultimately decide that they are not wrong. But if a student is willing to question his or her previously held assumptions, I consider that success in the classroom. And if they learn a few things along the way, that’s even better.”

Below, three professors talk about their research, life in the classroom, and the professional questions that engage them.

“I am always thinking about what constitutes the ‘politics’ of art and how art becomes the occasion for politics,” says Associate Professor of Art History Mary Coffey. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Mary Coffey

Associate Professor of Art History

I have two projects currently. The first is a book-length study of José Clemente Orozco’s mural, The Epic of American Civilization, at Dartmouth. The second focuses on a traveling exhibition, “The Great Masters of Mexican Folk Art.”

My book on Orozco follows directly from my teaching. I teach the mural in all of my courses, and for several years I have directed students in deep visual and historical analysis of the mural in term-long research projects. Additionally, the work I have done with the Hood Museum of Art, the library, and the Manton Foundation to promote the mural and to improve the didactic materials we offer here and online has informed my evolving understanding of the mural.

***

I am always thinking about what constitutes the “politics” of art and how art becomes the occasion for politics. I am interested in this question specifically with respect to how students respond to the public art on Dartmouth’s campus, but more broadly I am curious about where we locate politics—in the artist’s intentions, in the work itself, in the viewer’s reaction to it, in the institutional dynamics that frame it, in the discourses about the work that evolve over time or that cohere at a particular moment. Every time a controversy over art erupts, I find myself asking what is really at stake here and how or why has this particular work of art become the occasion for the expression of discontent?

“Most advances are made when researchers suspend their preconceptions and get on with it, even when the risk of failure is high,” says Associate Professor of Anthropology Nathaniel Dominy. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Nathaniel Dominy

Associate Professor of Anthropology

I am studying how, when, and why the human pygmy phenotype evolved. This project complements three of my courses—“Introduction to Biological Anthropology,” “Hunters and Gatherers,” and “Human Functional Anatomy.”

My former PhD adviser, who is British, used to say “let’s have a go” in response to any research idea. I used to question the value of this undiscriminating enthusiasm, but now I recognize it as a great intellectual strength. Most advances are made when researchers suspend their preconceptions and get on with it, even when the risk of failure is high.

The moment I committed to my field was the first time I caught a free-falling, anesthetized monkey. My undergraduate adviser darted it in order to study its physical condition, in particular its teeth. At the time, I was only dimly aware that my professors had lives outside the classroom. From that point forward, I was enthralled with the idea of integrating teaching with research on wild primates.

***

I think about sleep when I can’t sleep—why is the daily duration of human sleep universal? Tanzania’s Hadza hunter-gatherers are substantially more active than the average American, and yet the duration of their sleep is similar despite being poorly insulated from cool nighttime temperatures.

“There is truly something spontaneous and not entirely replicable about the classroom experience,” says Associate Professor of History Leslie Butler. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Leslie Butler

Associate Professor of History

I’m currently working on a book that uses debates over the “woman question” (the phrase Victorian- Americans and Britons employed to refer to women’s role in the family, society, economy, and the polity) as a way to explore the meaning of democracy in 19th-century American thought.

My research always informs what I do in the classroom. It shapes the questions that animate my syllabi and it affects the readings I assign or emphasize. This winter, for example, I’m offering a new upper-level seminar on debating democracy in the 19th century. Tocqueville’s monumental Democracy in America will be a central text, so I can’t wait.

***

My most formative influence as an American historian has surely been my graduate adviser, David Brion Davis ’50. Davis, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of American slavery, encouraged me to take seriously not just the formal ideas but also the less formal values, beliefs, assumptions, and preoccupations of historical actors. His own work provides a model of historical scholarship as a moral endeavor.

My favorite teaching moments are when I can palpably feel students getting excited while discussing a particular text or thinker or idea. There is truly something spontaneous and not entirely replicable about the classroom experience.