This is the third in a three-part series about professors and their work. Here’s a look atpart one and part two.

“I’m interested in figuring out why writers like Faulkner (and Hemingway, Cather, even Toni Morrison) return so often to Native American themes,” says Associate Professor of Native American Studies Melanie Benson Taylor. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Melanie Benson Taylor

Associate Professor of Native American Studies

I’m currently writing a book called Faulkner’s Doom, which revisits the entire canon of this American literary giant to reassess the centrality of indigenous tropes in his world and work. Like many influential American authors, Faulkner doesn’t portray Native peoples as “real” Indians—and my work is not designed to indict him for that, or even to set the record straight about what “real” Mississippi Chickasaws were like. Instead, I’m interested in figuring out why writers like Faulkner (and Hemingway, Cather, even Toni Morrison) return so often to Native American themes.

***

I was committed to literature from the moment I read my first words at the age of 3. Of course, growing up in a working-class environment, I had no conception of what a career in literary studies could possibly mean. In a romantic way, I thought I might just be “a writer”—until my junior year in college, when one of my English professors encouraged me to apply to doctoral programs in American literature. A whole new set of opportunities came into view for me then, and I never looked back.

Professionally, I sometimes ask myself, is anyone listening? Not necessarily to the literary scholars, but to the voices and experiences we strive to bring to light. Literature offers us a window into alternate worlds, but also affirms our shared humanity. In a world that grows continually more divisive and frenetic, I hope that we never lose the hypnotic and transformative power of a good book. If we let it, literature can be a pathway to humanity, compassion, and grace.

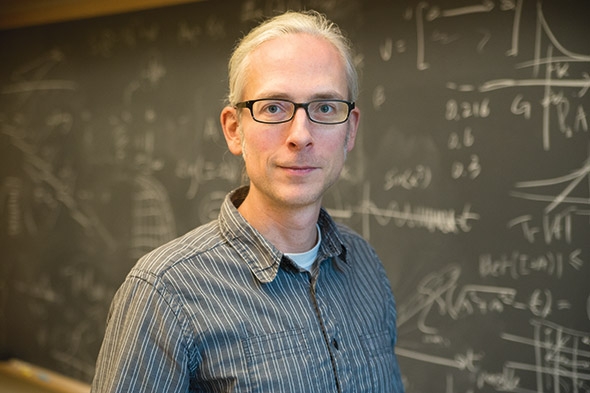

“To me, success as a scholar is contributing meaningfully to solving a problem in a way that helps society,” says Associate Professor of Mathematics Alex Barnett. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Alex Barnett

Associate Professor of Mathematics

My current research involves figuring out ways to solve how sound and light waves bounce from complicated structures like bumpy surfaces and micro-chips. Engineers already have crude ways to do this, but the ways I develop are faster and more accurate.

I teach a course on the connections between music and mathematics, and now I am doing a research project on acoustics: how the sound of footsteps gets transformed into a “water-dripping” sound by propagation along the long stone staircases at the Mayan pyramids in Mexico.

***

To me, success as a scholar is contributing meaningfully to solving a problem in a way that helps society. This is difficult, since there is such a long chain of events to go from algorithm to engineering to technology to product to improved lives, but I am one link in that chain.

Mentoring young students and researchers is very important, as well.

***

I grew up committed to physics—spending hours building electronic circuits and doing experiments. Then, after graduate school, I found that applied mathematics was a place where numerical computation could be explored deeply, and that one could work on a wider variety of problems in biology, engineering, medical imaging, etc.

“It is critical to consider that teaching happens in many places—not only in classrooms with undergraduate students, but also in research laboratories with graduate students who are integral to our learning community,” says Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Amy Gladfelter. (Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Amy Gladfelter

Associate Professor of Biological Sciences

My path into research science was a slow accumulation of multiple moments of pleasure in discovering new aspects of how cells work, the fun in sharing discoveries with others, and the creative challenges of translating data into models to explain some aspect of how the molecules of life act together.

I currently have 14 people whom I mentor in their research projects, so that means more than 14 projects, as most people have a few lines of inquiry going at the same time. These projects include work by undergraduates, PhD students, postdocs, and a research technician. All of these projects revolve around how cells are organized in time and space.

We study how cells make decisions about when to divide, and specifically we are interested in why cells that are genetically identical take different amounts of time to decide to divide.

***

It is critical to consider that teaching happens in many places—not only in classrooms with undergraduate students, but also in research laboratories with graduate students who are integral to our learning community.

I also think so much learning happens in independent studies in research laboratories—not simply course-associated labs—and only if there are active researchers/teachers are there spaces for undergraduate students to perform novel research and practice the skills of data analysis and interpretation so critical for the future.