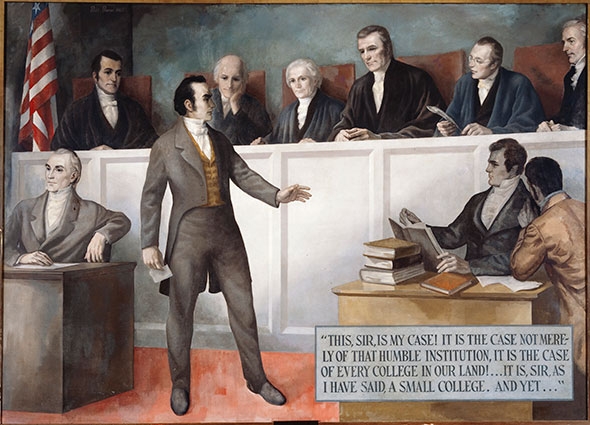

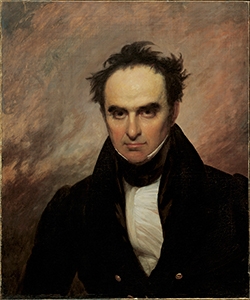

In honor of the Fourth of July, Dartmouth Now is republishing this story about one of America’s greatest speakers, lawmakers, lawyers, and diplomats, whose legendary career as an orator began at Dartmouth.

On July 4, 1800, Dartmouth junior Daniel Webster, Class of 1801, delivered the commemorative Independence Day oration in Hanover, the first in a long line of civic declamations.

“Countrymen, brethren, and fathers, we are now assembled to celebrate an anniversary, ever to be held in dear remembrance by the sons of freedom. Nothing less than the birth of a nation, nothing less than the emancipation of three millions of people, from the degrading chains of foreign domination, is the event we commemorate,” Webster began.

Dartmouth’s Daniel Webster CollectionThe Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College holds an extensive collection of the papers and artifacts of Daniel Webster, Class of 1801, housed, of course, in Webster Hall.

“We have the largest collection of Daniel Webster papers in the country,” says College Archivist Peter Carini. “That includes his top hat and socks and a vast array of things related to, belonged to, or were associated with him, from his boyhood up to his death.”

The late Dartmouth Professor Charles Wiltse spent more than 20 years, beginning in the 1960s and continuing well after his retirement in 1972, collecting, cataloging, microfilming, and editing Webster’s papers. The final volume of his 16-volume collection of The Papers of Daniel Webster, was published ceremoniously in 1989, highlighted with a speech by Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

Find more information about the Webster collection at the Rauner Special Collections Library website.

This was the opening riff by a man who would become one of America’s greatest speakers, lawmakers, lawyers, and diplomats, says Professor of History Emeritus Kenneth Shewmaker, editor of two of the 16-volume Papers of Daniel Webster. Rauner Special Collections Library holds one of the largest collections in the world of Daniel Webster papers, artifacts, and daguerreotypes.

In his July Fourth address, Webster continued at some length and with considerable flourish to celebrate the veterans of the Revolution, living or dead, to offer a paean of praise to George Washington, who had died just months before, and to celebrate the unifying authority of the U.S. Constitution, then just a decade old.

“The speech was very well received and met with applause,” says Shewmaker. “It was certainly unusual to be coming from an 18-year-old Dartmouth undergraduate, but that was because Webster had already earned a great reputation as a speaker and debater at the College.”

It was particularly remarkable coming from the man who later confessed that, when called on to speak before his classmates at Phillips Exeter Academy, he “became embarrassed and burst into tears.”

Webster, with his rural upbringing, didn’t fit in with the “city boys” at the prep school, so his father, Ebenezer, pulled him out and sent the boy to the Rev. Dr. Samuel Wood, Class of 1779, in Boscawen, N.H., to prepare the 15-year-old for Dartmouth.

Webster’s abilities quickly became apparent after Wood caught Webster sneaking into the woods to hunt, and ordered him to memorize 100 lines of Virgil by the next morning as punishment, Shewmaker says.

“The next day, Webster repeated the lines without difficulty, then volunteered to recite another hundred,” Shewmaker says.

Wood declared him “a very smart boy,” and turned to other work. “Webster said, ‘I have another 500, if you please.’ Wood, who had had quite enough, gave him the rest of the day off for pigeon shooting,” Shewmaker says.

He packed Webster off to Dartmouth six months later with the highest of recommendations. “I’m tired of you,” Wood reportedly said.

This ability served Webster well throughout his career.

“He had a fantastic memory—remarkable, really. If you go to Rauner and look at drafts of his speeches, they’re pretty sketchy,” Shewmaker says. “There are just a few words jotted down to prepare for his great speeches.”

But it was coming to Dartmouth, and specifically, becoming a brother in the United Fraternity, that opened the door.

“It’s important to understand that he wasn’t part of one of those drinking clubs that get into all sorts of trouble,” Shewmaker says. “These were primarily debating societies. They would debate, for example, the differences between Jefferson and Adams.”

At that time, current events and politics were not part of the curriculum. A college education was about the classics, theology, and recitation.

Now Webster’s classmates at Dartmouth were also his friends and brothers, so he was able speak without fear of ridicule, and could let his talents shine.

“One of his legacies from Dartmouth College is it turned him into the preeminent orator of his age, and in fact, one of the preeminent orators in American history,” Shewmaker says. “Really, from my point of view, the key to the whole rest of his career—the budding beginning—is there in the oration at Hanover of July 4, 1800.”

This story was originally published July 2, 2014, on Dartmouth Now.