The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., today launched the Early Warning Project for forecasting mass atrocities, developed jointly with Dartmouth’s John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding.

The initiative was set in motion by former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, head of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Genocide Prevention Task Force. A 2008 policy document from the task force included a call to develop an advanced risk assessment process to flag developing problems.

“By building a trusted system grounded by qualitative and quantitative analysis and the best available data, this system has the potential to drive a new policy agenda and a lasting impact on the ground and save lives before conflicts boil over,” Albright said of the system’s unveiling Monday.

One of the architects of the project was Associate Professor of Government Benjamin Valentino, coordinator of the War and Peace Studies Program at the Dickey Center. Valentino, the author of Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century, was a consulting expert for risk assessment on the task force, which was chaired by Albright and former Secretary of Defense William Cohen.

(Photo by Eli Burakian ’00)

Based on task force recommendations, the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum invited Valentino to convene an interdisciplinary group of experts to imagine how an early-warning system might work. The central concept was to create a completely open risk-analysis system built on the massive amounts of public data available from institutions such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the World Health Organization, and drawing on expert opinion from analysts and academics around the world, Valentino says.

Countries at Risk

The Early Warning Project has identified the 10 countries most at risk of experiencing a new occurrence of mass killing:

- Myanmar

- Nigeria

- Sudan

- Central African Republic

- Egypt

- Congo-Kinshasa

- Somalia

- Pakistan

- South Sudan

- Afghanistan

Other countries of concern include:

- Burkina Faso, which moved from just beyond the top 30 in 2014 to 16th in this year’s list.

- Ukraine, which ranked as a negligible risk in 2014 and is 20th in this year’s assessment.

- Libya, which climbed from about the 90th spot in 2014 to 24th in 2015.

The Early Warning Project was jointly created by the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide and the Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth College. The project launched on Sept. 21, but has been run in a test phase in 2014 and 2013.

It consists of two open and collaborative elements: a statistical risk assessment which uses a broad range of measures to rank countries that are at risk for mass atrocities, and a “wisdom-of-crowds” opinion pool updated with live expert feedback.

“The idea is that everything is transparent, all code is open source, the data modeling methods are clearly documented and available to everyone, experts can communicate with each other, and everything is tracked over time,” he says.

The aim is to give anyone, including governments, advocacy groups, non-governmental organizations, and at-risk populations reliable predictions of potential mass killings and victimization of civilians, to create more opportunities for action,” Valentino says.

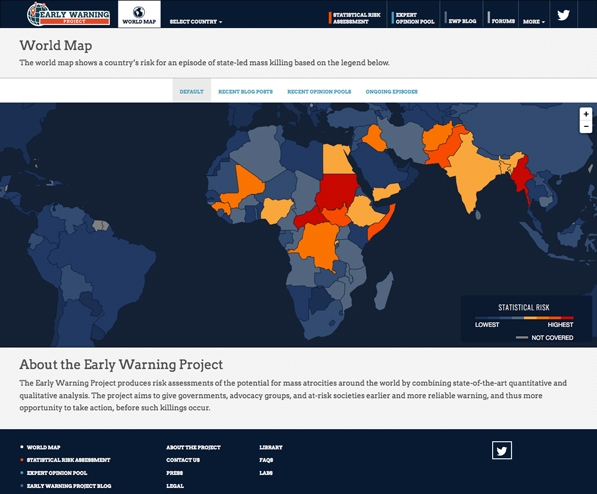

The Early Warning Project website, the prototype of which was developed by Dartmouth’s DALI Lab with support from the Neukom Institute for Computational Science and the Department of Computer Science, uses an interactive map as a navigational tool. Countries are displayed in colors based on assessed risk, and when users click on a country, the site displays relevant material. There is also a blog where analysts can share ideas and opinions, and other graphic displays of countries’ risk factors that show risk levels based on three data-modeling systems and the overall average of risk.

A key step along the path to this week’s launch was the Dickey Center’s inaugural Leila and Melville Straus ’60 Symposium in the fall of 2014, which brought 20 experts from the Holocaust Memorial Museum, the tech and defense industries, and a variety of universities to consider how to improve upon assessment processes used in the project. The keynote speaker at a public session of the symposium was Sarah Sewall, Undersecretary of State for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights.

Daniel Benjamin, the Norman E. McCulloch Jr. Director of the Dickey Center, says, “I’m really pleased with the way this partnership with the Holocaust Museum has developed and that Dickey has been able to play a central role in the project. Preventing genocides and mass atrocities is one of the greatest challenges in international affairs. This effort will advance our predictive capabilities and build public interest, and it’s exactly the kind of policy-relevant work that Dickey seeks to produce.”

Cameron Hudson, director of the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide, called the project a critical tool to spur action at the early signs of risk for mass killings and victimization of civilians.

“From past genocides in Darfur, Bosnia, Rwanda, and the Holocaust, we have learned what the clear early warning signs are that precede mass violence. Tracking those indicators in at-risk countries around the world will, for the first time, allow us to look over the horizon to implement smarter, cheaper, and more effective policies that prevent mass violence,” Hudson said.

It was the mass killings in Rwanda that set then-student Valentino on the path to trying to understand how genocide and atrocities can happen, and to find ways to prevent them.

”It is still deeply mysterious and troubling to me why anyone would decide to take the lives of hundreds of thousands of unarmed civilians,“ Valentino says.

”It seems to me one of the central ethical questions of our day is how to understand it and how to try to stop it. That’s what got me involved in the forecasting business and this is really the first time I have had the opportunity to do something for the public, rather than just the government, to try to make some contribution to anticipating these events and then ultimately, hopefully, preventing them," he says.