A revolutionary breakthrough is underway at Dartmouth’s Thayer School of Engineering, an innovation that may usher in the next generation of light-sensing technology with potential applications in scientific research and cell phone photography.

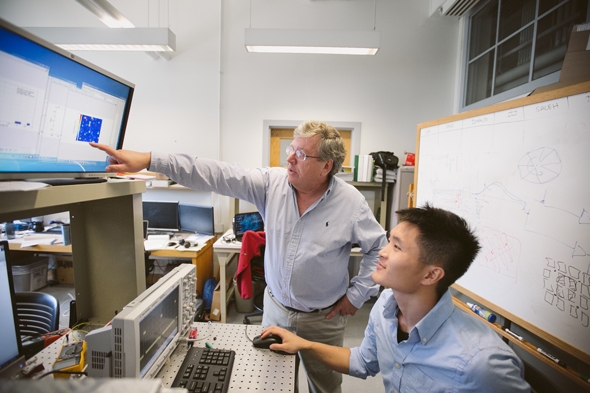

Professor Eric Fossum and Thayer PhD candidate Jiaju Ma have worked together on the project for more than three years, are co-inventors of the new pixel, and shared authorship of a June 2015 paper on their invention. (Photo by Robert Gill)

Thayer’s Eric Fossum—the engineer and physicist who invented the CMOS image sensor that made possible the billions of cell phone and digital cameras in use today—joined forces with Thayer PhD candidate Jiaju Ma in developing pixels for the new Quanta Image Sensor (QIS).

The professor and student have worked together on the project for more than three years, are co-inventors of the new pixel, and shared authorship of a June 2015 paper on their invention, published in IEEE Electron Device Letters.

Read More:

Q&A with Cell Phone Camera Inventor Eric Fossum

Dartmouth Professor Eric Fossum Elected to National Academy of Engineering

Their new sensor has the capability to significantly enhance low-light sensitivity. This is particularly important in applications such as “security cameras, astronomy, or life science imaging (like seeing how cells react under a microscope), where there’s only just a few photons,” says Fossum.

“Light consists of photons, little bullets of light that activate our neurons and make us see light,” he says. “The photons go into the semiconductor [the sensor chip] and break the chemical bonds between silicon atoms and, when they break the bond, an electron is released. Almost every photon that comes in makes one electron free inside the silicon crystal. The brighter the light, the more electrons are released.”

Fossum says one of the challenges in the QIS is to count how many electrons are set free by photons and thus effectively count photons. This is particularly important in very low light applications, such as in life science microscopy, photography, or even possibly quantum cryptography and what’s being called the “Internet of Things.”

“When we build an image sensor, we build a chip that is also sensitive to these photons. We were able to build a new kind of pixel with a sensitivity so high we could see one electron above all the background noise.”

The new pixels are considerably smaller than regular pixels since they are designed to sense only one photon, but many more are placed on the sensor to capture the same number of total photons from the image. “We’d like to have 1 billion pixels on the sensor and we’ll still keep the sensor the same size,” says Ma.

These new pixels are able to sense and count a single electron for the first time, without resorting to extreme measures, such as cooling the sensor to minus 60 C and/or avalanche multiplication. “Avalanche multiplication may be thought of as an electrically induced chain reaction, but the strong electric fields necessary lead to reliability issues and it is difficult to make small pixels,” says Fossum.

“We deliberately wanted to invent it in way that is almost completely compatible with today’s CMOS image sensor technology so it’s easy for industry to adopt it,” says Fossum. Engineering its size is a step in that direction.

“The question was how to build this in a current, commercially accessible, not-too-expensive CMOS process.” he says. “You use all the tricks you can think of. Being able to measure one electron is fundamental from a scientific point of view and we were able to do it without a ‘Manhattan Project.’ ”

Other challenges his group is working on involve reading out a billion pixels hundreds or thousands of times each second without dissipating too much heat, and also creating images from all the data that is collected.

“This is a proof of concept,” says Ma—in other words, a real-world demonstration of its feasibility.

Fossum says the image sensor community seems receptive to the new technology. “Engineers in industry are continuously improving the state of the art. They have to worry about the next product or the product after the next product. They don’t have the luxury of thinking like, ‘What are we going to do 10 years from now?’ That’s where I’m happier thinking—in that timescale.”

The QIS project has been funded by the Silicon Valley company Rambus Inc., where Ma has served as an intern during the past two years. “A company representative offered some extraordinarily high praise for him,” says Fossum, “calling him a ‘superstar intern.’ We hope to continue our collaborations with Rambus in the future.”