College students have been debating each other competitively for centuries, and at Dartmouth the tradition is still very much alive.

Students who like to argue in public can join the parliamentary debate team, a familiar format that relies on extemporaneous speaking skills, a sense of humor, and persuasive rhetoric.

Or they can sign up for a grueling, research-based activity called “policy debate.”

Unlike parliamentary debaters, policy debaters belong to Dartmouth’s Forensic Union and marshal reams of evidence to support their arguments. Topics typically relate to U.S. domestic or foreign policy. The more written research competitors gather, the faster they must read it aloud within allotted time frames. Word-packed presentations are almost impossible for an average listener to follow. But judges understand this arcane language, and so do contestants and coaches.

Dartmouth’s policy debate team has a new coach, John Cameron Turner ’03, who aims to bring fresh energy to the program. He’s training eight debaters who travel to tournaments and compete as two-person teams.

This year’s intercollegiate topic: Should the United States significantly reduce its military presence in one or more of the following: the Arab States of the Persian Gulf, the Greater Horn of Africa, and Northeast Asia?” Every college team must argue both the affirmative and the negative. “Research for either side by a top-level debater is equivalent to a Master’s level project,” says coach Turner.

At practice, speaking in favor of reducing military presence in Djibouti, Abla Belhachmi ’17 argues that American intervention in Africa is misguided. “It’s a new manifestation of the fiction that Africans cannot build their own nation states without American help,” she says.

Opposing demilitarization, Tyler Anderson ’18 makes a scathing critique of U.S. foreign policy and politics overall. Limited reforms of military presence, he argues, merely consolidate the United States’ role as a neo-colonial power. In high school tournaments, Anderson and his partner adopted what he calls an “alternative style of debate,” weaving hip-hop and rap into their presentations, which were sometimes even accompanied by music.

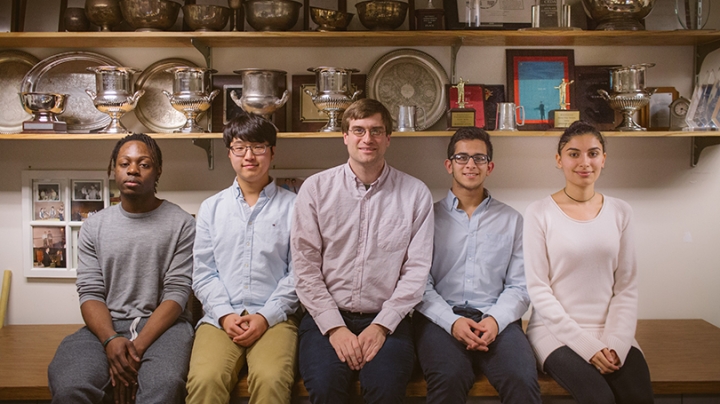

“Some judges were OK with that; others weren’t,” Anderson says. He laments that college teams tend to have fewer people of color than high school teams. But Dartmouth’s Forensic Union is becoming increasingly multi-cultural. In addition to Belhachmi and Anderson, the active roster includes Ryan Spector ’18, Pirzada Ahmad ’18, Kai Yan ’18, Imanol Avendano ’18, Lillian Jin ’19, and Daehyun Kim ’19. So far this year they have competed in Georgia, Kentucky, Massachusetts, North Carolina, California, and Texas. Other members of the Forensic Union who have debated in the past two years include John Martin ’17, Deep Singh ’17, Daniel Kreus ’16, Jackie Chen ’16, and Noah Cramer ’16.

Coach Turner is ramping up recruiting at the summer debate institutes held on campus every year, and also at high schools around the country. He sees “a significant effort on the part of high school and college debate to generate more diversity and inclusivity.”

Opening doors to students traditionally underrepresented on debate teams has been a lifelong pursuit of one of Dartmouth’s best debaters, Leonard Gail ’85. He helped found the National Association of Urban Debate Leagues, whose mission is to teach urban students to debate, empowering them to think, communicate, and collaborate. In Gail’s time, Dartmouth’s Forensic Union filled glass cases with silver trophies. But major victories have been harder to come by in recent years. Gail thinks Coach John Turner can “get us back to the glory days.”

An attorney in Chicago, Gail says debating at Dartmouth influenced “what I do for a living, how I think, who my friends are, even who I married. Academic debate is the most formative thing in my life, bar none.”

Dartmouth’s current debaters share Gail’s passion.

“True, debate is like a cult,” says Spector.

“Without the religious affiliation,” chimes in Anderson.

“Right,” agrees Belhachmi. “But we do have our own language.”

Coach Turner says all good debaters graduate not only as fast talkers, but skilled thinkers.

“I’d like to think that debate is rooted in a bit of humility,” he says. “You know, your perspective on the world is partial, and one that you should always be willing and in some ways hoping to engage with others.” His team hopes to qualify for three national championship tournaments in March.