March 29, 2016

For many immigrants in this country, anti-immigration rhetoric is not just something that you hear on the campaign trail but a reality. In fact, about a third of U.S. states, have had restrictive laws directed at undocumented immigrants in place since the late 2000s. As a result, many Latinos have become averse to moving to these states according to a new University of Washington – Dartmouth study just published in the Annals of the American Association of Geographers. (A copy of the study is available upon request).

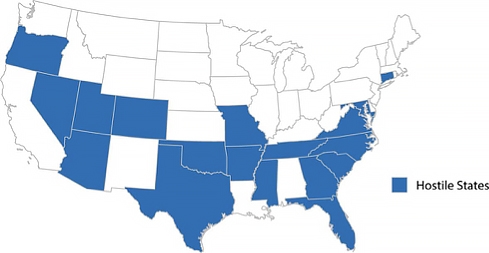

To examine the effects of state-scale immigration enforcement on internal Latino migration patterns, the study uses data from the decennial census in 2000 and from the American Community Survey for 2005-2010. Adapting earlier research on Latino migration by Arjen Leerkes, James Bachmeier and Mark Leach, the research classifies states into two groups: “hostile states,” which have enacted laws that are restrictive in some way (i.e. Ariz., Ark., Colo., Conn., Fla., Ga., Md., Miss., Mo., N.C., Nev., Okla., Ore., S.C., Tenn., Texas, Utah, Va.) and all others (“non-hostile states).”

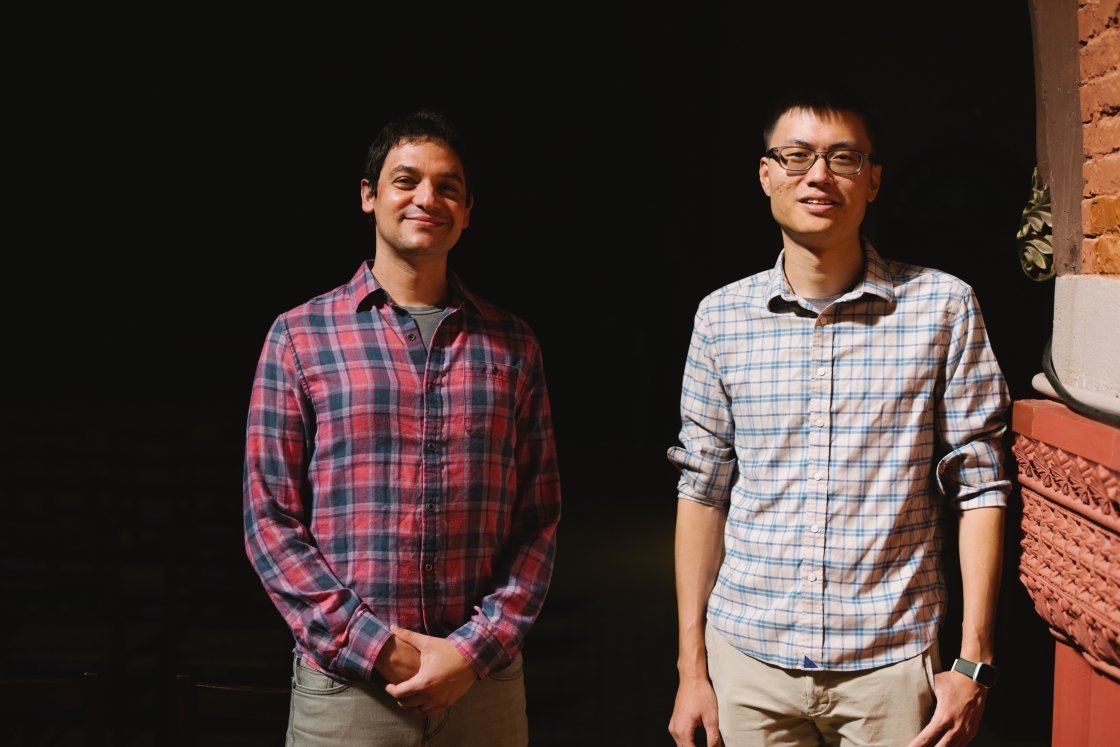

Image  |

| Hostile states. Source: Leerkes, Leach, and Bachmeier (2012) (Color figure available online). [Figure is from the AAAG article]. |

Examples of hostile state laws currently in place are universal employment verification, which makes it hard for immigrants in the U.S. without permission to obtain the authorization to work, and mandatory legal status checks for state licensing services, which makes it more difficult for the unauthorized to obtain driver’s licenses or access other state services. One of the most extreme examples of hostile state laws was Arizona’s SB1070 in 2010, which attempted to criminalize the presence of unauthorized immigrants in the state. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, vacated most of the provisions in SB1070 and that of copycat laws passed by other states in June 2012.

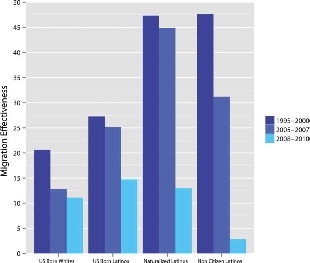

The study looks at the migration patterns of three sub-groups of Latinos— U.S.-born Latinos, naturalized Latinos and non-citizen Latinos, and for a control group of U.S.-born non-Latino white group, during three periods: 1995 to 2000; 2005 to 2007; and 2008 to 2010.

• Between 1995 to 2000, the states that were yet to pass laws making life difficult for unauthorized migrants, attracted Latinos disproportionately. In the 1995-2000 period, nascent hostile states experienced a net gain of 47 for every 100 naturalized and non-citizen Latinos, as compared to U.S. born whites during that time, who had a net gain of 20 people per 100 movers in and out of future hostile states.

• For the 2005-2007 period, at the onset of the Great Recession, population change due to migration dropped a bit for all four groups but still remained relatively robust.

• During the 2008-2010 period when hostile state policies were now in effect, migration redistribution for both U.S.-born and naturalized Latinos fell dramatically to levels close to those of U.S.-born whites. Most notably, in 2008-2010, the redistribution effect of non-citizen Latinos to hostile states came to a halt. Non-citizen Latinos were opting not to move to states that had restrictionist policies in place.

Image  |

| Observed migration effectiveness: Hostile states. Source:Public Use Microsamples from 2000 U.S. decennial census, and the 2005–2010 annual American Community Survey (Ruggleset al. 2015). Restricted to flows between the lower forty-eight states and persons between eighteen and sixty-five. Calculations by author (Color figure available online). [Figure from AAAG article]. |

“Like almost all immigration legislation, these state-scale statutes have had intended and unintended consequences. They have reduced the attractiveness of these states to the unauthorized, but they have had a serious dampening effect on the migration patterns of Latinos with rights associated with citizenship, ” said study co-author, Richard Wright, Professor of Geography at Dartmouth College.

The state-scale immigration policies deterred internal migration for all Latinos. Latinos with citizenship, who avoided hostile states, may have been trying to minimize the potential for elevated levels of discrimination or if they are part of a mixed-legal status family, they may not have wanted to put their family in a more vulnerable environment.

The geographic pattern of states with immigration policies aimed at making life difficult for the unauthorized from the late 2000s still applies today. Latinos however, are not the only marginalized group in U.S. history for which migration has been impacted by state policies, as a similar effect took place with the Great Migration of African Americans in the early and middle decades of the 20th century during which blacks moved to the north and the west to escape Jim Crow Laws and the racial violence in the south. The Latino migration patterns in the study are unlikely to be reversed unless states change their policies.

Available to comment on the study are co-authors: Mark Ellis, Professor of Geography and Director of the Northwest Federal Statistics Research Data Center at the University of Washington at: ellism@uw.edu; and Richard Wright, Professor of Geography, Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies, and the Orvil E. Dryfoos Chair of Public Affairs at Dartmouth at: richard.a.wright@dartmouth.edu. Matthew Townley, a graduate student in the department of Geography at the University of Washington, also served as one of co-authors of the study.

###

Broadcast studios Dartmouth has TV and radio studios available for interviews. For more information, visit: Broadcast Studios