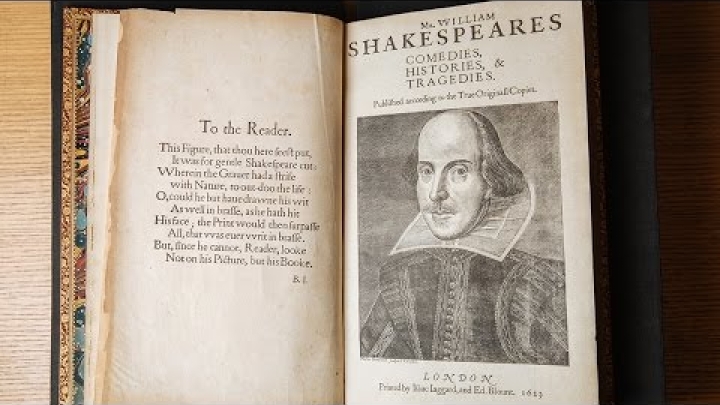

Seven years after William Shakespeare’s death in 1616, two actors from his King’s Men troupe compiled his greatest hits into a collection known as the First Folio—36 plays, from The Tempest to Cymbeline, that form the core of what we traditionally think of when we think of Shakespeare.

Of the 750 copies printed of the First Folio, less than a third survive. The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, has about 80 copies, many of which are currently on tour throughout the United States as part of celebrations of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

And one, given to the College as part of a bequest from Allerton Hickmott, Class of 1917, and his wife, Madelyn, is the second-most requested book at Rauner Special Collections Library (after a first edition of The Book of Mormon).

“It’s very rare to have any, so the fact that we have one is sort of amazing,” says Shakespearean scholar Brett Gamboa, an assistant professor of English.

Even more rare, Gamboa says, is that, at Dartmouth, students, faculty, and the community can view the First Folio not under glass, but up close.

“It’s sort of breathtaking, not only because it exists and exists here, but that students every day can interact with it,” he says. “I don’t mean just look at it, but thumb through the pages and see the liner notes and find their favorite plays and passages in a copy of the First Folio.”

“It’s sort of breathtaking, not only because it exists and exists here, but that students every day can interact with it,” says Assistant Professor of English Brett Gamboa. (Photo by Robert Gill)

On a recent afternoon, students in Gamboa’s “English 15: Shakespeare” course get to do just that. Librarians Morgan Swan and Laura Braunstein have brought the Folio—along with a sampling of other contemporaneous volumes—on a special visit to Gamboa’s classroom.

Uncasing the books on a table in the front of the room, Swan tells the group of 14 students, “This is pretty informal—you should leave your drinks and pens and food, but otherwise come on down. This is sort of a rare outing. Usually you have to come to us.”

Swan tells the class about the publication history of Shakespeare’s plays—how during his lifetime he and his players were more interested in retaining the exclusive ability to perform his works than to publish the scripts widely.

“If you were a printer back then in London and you were the first person to print a play or a book, then you owned the copyright,” Swan says. “Printers would send guys to stand among the groundlings in front of the stage to remember everything they could and take it back and then, OK, we’ve got Hamlet, boom! That’s why the earliest quarto of Hamlet is called the bad quarto. It’s just laughable—whole sections missing.”

The First Folio, printed later, was something different altogether. The actors John Heminges and Henry Condell were concerned about Shakespeare’s reputation—and their own, Swan says. So they decided to create a definitive edition of the plays.

“They went around and created this consortium of all the printers out there who had held copyright to all the plays that had been published. And then they brought in their own working copies that they had used when they were acting—when they actually played the role of Hamlet.”

“The First Folio is really important because if this hadn’t been published, half of Shakespeare’s plays would be lost,” Swan says. “Only 18 plays had been printed up to that point.”

After Swan’s presentation, the students have a chance to examine the book itself and ask questions ranging from the order of the plays in the volume to why the paper in the First Folio has held up so well over 393 years. (Answer: The linen and cotton fiber of 17th-century paper is less acidic than modern wood pulp paper.)

“To have the Folio brought directly to our classroom and to have it be really tangible is just a weirdly transcendent experience,” says Hannah Mazonson ’18. “It’s incredibly cool getting to flip through it and compare what the text looks like to what we’re reading in class.”

That’s exactly the kind of experience Gamboa, Braunstein, and Swan want students to have. Asked why Rauner Library lets people handle documents like the First Folio, Swan says, “We are very conscious of the fact that every time someone handles it, it minutely deteriorates the item. But we’re so committed to the educational, experiential act that we feel like being able to engage physically with the object has a value that you can’t reproduce if it’s behind glass or you have someone just talking at you about it.”