Climate change is having a clear impact on the seasons in New Hampshire, according to a new study by Dartmouth researchers and their colleagues.

“Warming of the Earth’s climate system has had varying degrees of impact around the world, with especially dramatic impacts in the Arctic and regions vulnerable to sea level rise. The impacts in New England are clear but perhaps seem more subtle,” says Mary Albert, a professor of engineering at Thayer School of Engineering and a member of the study team.

The study notes that recent winters have been ending sooner and the transition period between winter and spring has been getting longer. The vernal window, as this transition time is called, is opening earlier as the daily average temperature rises above freezing.

“Based on the data collected, we can now project this interval will lengthen as we see warmer and less snowy winters,” says study team member Alden Adolph ’11, a PhD student at Thayer School of Engineering.

Adolph says a longer vernal window has important implications for ecosystems, with an earlier flowering of plants and changes in the timing of the emergence of insects such as ticks and black flies and also in the timing of the migration of birds and fish.

The three-year study, funded by the National Science Foundation and published in the journal Global Change Biology, documents changes in seasonal transitions in the Granite State. Researchers from Dartmouth were part of the team that included scientists from other New Hampshire universities, the U.S. Forest Service, and the National Center for Atmospheric Research, supported by more than 100 volunteers.

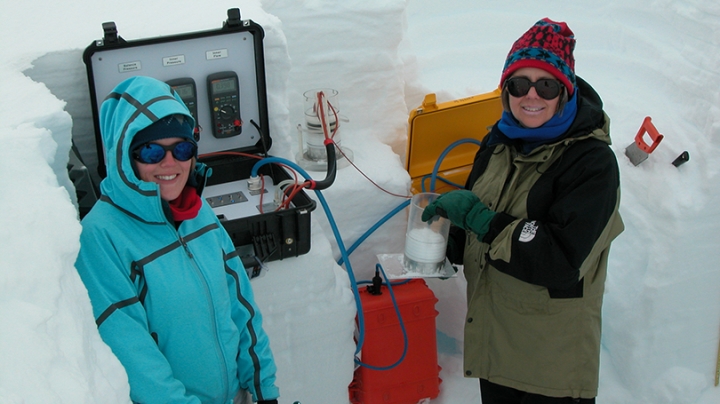

Using a statewide network of sensors, the scientists monitored climate, snow, soils, and streams over a three-year period. These observations were analyzed, computer modeled, and supplemented with satellite data.

The study notes that snowpack disappearance occurred simultaneously with rapid soil warming. When snow covers the ground, sunlight is bounced off and cannot warm the earth beneath. “As the highly reflective snow retreats earlier, it reveals the darker dirt or grass underneath that absorbs more of the incoming radiation,” Adolph says. “This increasingly heats things up, accelerates the melting, and mud season ensues.”

“Our data provide additional evidence that the season for natural snow on the ground is ending earlier, and demonstrates that the loss of snow then impacts the soil and its associated ecosystems,” says Albert. “Our planet is a system of systems; as an integral component of the climate system, snow is an important component and its loss affects the state of the soil and its associated ecosystems, even here in New Hampshire.

“Over recent decades, the planting zones map that we see on the back of seed packets has been changing as the plant hardiness zones are moving north, and the ski industry here has had to implement more artificial snow-making,” Albert says.

The earlier melt also results in the closure of some recreational hiking trails. “You can’t hike in the mud because it damages the paths,” says Adolph. “The timing and duration of maple sugaring can be affected and roads become hard to drive on, hindering logging operations.”

While the data showed that the snow is disappearing sooner, the timing of when the trees begin to sprout leaves—which marks the close of the vernal window—has remained fairly constant across the state.

“It's a combination of sunlight and temperature, with sunlight playing a more important role in green up than in the other transitions we studied,” Adolph says. “Based on the time of year and the position of the Earth, there will always be a given amount of sunlight. Even if the winter is warmer, you are still not going to have much more sunlight than the year before.”

The study covered three years—2012, 2013, and 2014—that represented the expected range of seasonal climates. “The first year was unseasonably warm, the third year was quite cold, and 2013 was moderate compared to a 30-year climate record,” Adolph says.

To ensure the validity of the study, the researchers included a variety of regions within the state. “Near the seacoast we had more mild temperatures, and in northern New Hampshire, we sampled the high mountain areas that were much colder and much snowier,” Adolph says. “This gave us two ways of looking at different types of temperatures and snowfall conditions, both geographically and over time.”

“What we have learned from the study may enable us to predict what might happen in the future, given warmer temperatures and decreasing snowfall,” she says. “It is a starting point, and collecting more data over time and continuing analysis would help us firm up these conclusions.”

Adolph says she hopes the research will inspire similar studies in other regions. “We were focused on this little area, and it would be nice to see if these types of conclusions hold across a broader context. We’d love for people to take these ideas and apply them in different parts of the world.”