May 10, 2017 – A Dartmouth-led study finds that volunteer-based state legislatures by their very nature, may perpetuate gender inequality in political representation. Family responsibilities appeared to disproportionately affect female legislators than their male counterparts, as women often take on more family obligations for their household, which in turn, compete in time with their legislative responsibilities. The findings were recently published in Socius. (A pdf of the study is available upon request).

In a volunteer or citizen-based state legislature for which there is no compensation and a lack of resources or staff, members must draw on their own personal time to fulfill their role as a legislator. Dartmouth’s qualitative study focused on the experiences of 17 women state legislators in N.H., who on average, were just over 60 ½ years old, married and had three children, many of whom were under 18 and still living at home. Two-thirds of the women in the sample spoke about the stress of juggling work-family obligations with their legislative duties. Respondents explained how they often were forced to choose between attending committee meetings and staying late to vote versus leaving in time to take care of loved ones. When filibustering came into play in the state legislature, women were less likely to be able to wait it out for legislation to be brought to a vote, whereas, men were more likely to be able to stay until a filibuster came to a close.

To juggle their responsibilities, women legislators adopted coping strategies such as bringing their children with them to legislative meetings but risked potential ridicule in the process. They often found themselves at a disadvantage, where they simply could not participate as fully in the political process due to the demands and scheduling conflicts associated with child or elder care. Many women in the sample discussed feeling guilty for missing family time to perform legislative work. Some stated that they felt like they weren’t being “good mothers,” as defined by gender norms. In prioritizing their work-family and legislative responsibilities, they ended up putting themselves last with little to no personal time.

In addition, two-thirds of women legislators indicated that their work seemed to be devalued in comparison to paid employment. Some women reported that their spouses did not seem to take their role as a legislator seriously given that the work was not paid or contributing to the livelihood of the family and was therefore, perceived as if it was charity.

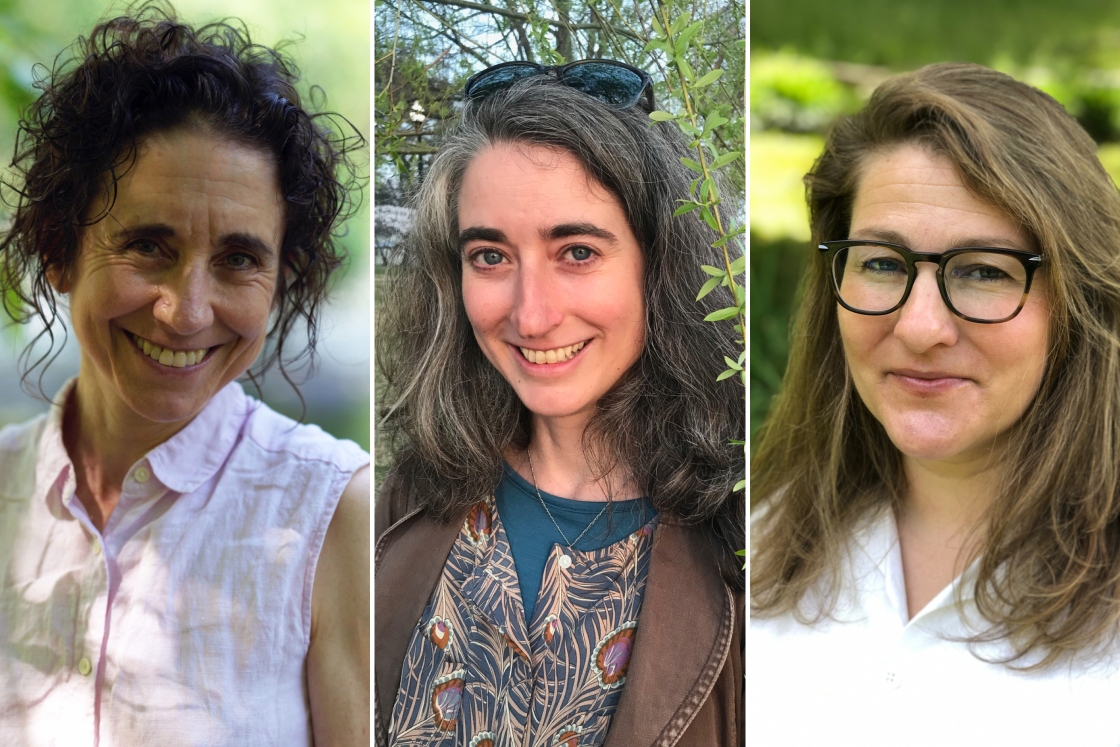

“So even though we began this project thinking that the volunteer aspect of the legislature would actually lower the barriers of support for women’s entry into the political sphere, the unpaid and often undervalued nature of the work, actually may actually heighten them,” says co-author Kathryn J. Lively, a professor of sociology at Dartmouth.

With over two-thirds of the state legislatures in the U.S. falling somewhere in between a “professional” and “volunteer” system, N.H. is just one of many citizen-based legislatures, where women legislators may be experiencing the tensions between legislative and work-family responsibilities. Instituting changes such as by scheduling meetings and votes during times that are more agreeable for all, would help address some of the political inequities and enable women to participate more fully as legislators. Women’s representation in politics however, may continue to be constrained if systematic barriers are not addressed from within both a state and national level.

Lively is available for comment at: kathryn.j.lively@dartmouth.edu.

The study was co-authored by Morgan C. Matthews, a graduate student in sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who conducted the study as part of her honors thesis during her undergraduate education at Dartmouth.