August 24, 2017 — The intensification of winter storm activity in Alaska and Northwestern Canada started close to 300 years ago and is unprecedented in magnitude and duration over the past millennium, according to a new study from Dartmouth College.

Image  |

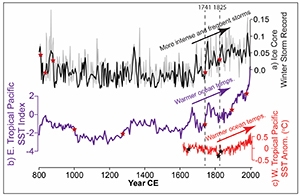

| Comparison of the composite North Pacific ice core sodium record with the Eastern tropical Pacific record (Conroy et al. 2009) and the Western tropical Pacific record (Abram et al., 2016) |

The research, an analysis of sea salt sodium levels in mountain ice cores, finds that warming sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean have intensified the Aleutian Low pressure system that drives storm activity in the North Pacific.

The current period of storm intensification is found to have begun in 1741. According to researchers, additional future warming of tropical Pacific waters – due in part to human activity – should continue the long-term storminess trend.

“The North Pacific is very sensitive to what happens in the tropics,” said Erich Osterberg, an assistant professor of earth sciences at Dartmouth College. “It is more stormy in Alaska now than at any time in the last 1200 years, and that is driven by tropical ocean warming.”

While the Aleutian Low pressure system sits over Southcentral Alaska in the winter, it can impact weather across the North American continent.

“Storminess in the North Pacific not only impacts Alaska and Northwestern Canada, it creates colder, wetter and stormier weather as far away as Florida,” said Osterberg.

The analysis focuses on two ice cores drilled in 2013 from Mount Hunter in Alaska’s Denali National Park, and an older ice core from Canada’s Mount Logan. The ice cores, each measuring over 600-feet long, offer glimpses into over a thousand years of climate history in the North Pacific through sea salt blown into the atmosphere by winter ocean storms.

The two ice cores from Denali benefited from high levels of snowfall, providing what Osterberg says is “amazing reproducibility” of the climate record and giving the researchers exceptional confidence in the study results.

“That’s the other remarkable thing about this research,” said Osterberg, “not only are we seeing strong agreement between the two Denali cores, we are finding the same story of intensified storminess recorded in ice cores collected 13 years and 400 miles apart.”

While 1741 is noted as the year the current intensification began, the paper also references an increase in storminess in the year 1825. According to the paper, warmer tropical waters since the mid-18th century can be the result of both natural variability and human-driven climate changes.

“There is no doubt that warming tropical ocean temperatures over the last 50 years is mostly caused by human activity,” said Osterberg, “a really interesting question is when you go back over hundreds of years, how much of that is anthropogenic?”

Beyond human activity, tropical sea surface temperatures further back in time are affected by volcanic eruptions, changes in the intensity of sunlight and natural events like El Niño.

“The reality of the science is that our changing climate is driven by human causes on top of natural cycles, and we have to disentangle these things,” said Osterberg. “This becomes even more critical when predicting climate change over a specific region like Alaska instead of the whole globe averaged together.”

Researchers are still waiting to analyze the last 10 meters of the Denali ice cores. The remaining portions could offer information on thousands more years of climate history, but are so compressed that they will require the use of advanced laser tools.

The paper was published last month in Geophysical Research Letters.