Nov. 28, 2017 – Nationalism associated with international sporting events like the World Cup may increase state aggression according to a study published in International Studies Quarterly.

“The findings from my research indicate that countries tend to behave more aggressively in international affairs after they experience surges of nationalism from international sports,” says Andrew Bertoli, a U.S. foreign policy and national security fellow at the Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth.

The research presents case studies where nationalism from sporting events led to military or political conflict between countries, such as the 1969 Soccer War and the 2016 English-Russian Euro riots. It also looks at how past militaristic leaders like Hitler have used this type of nationalism to increase public support for aggressive foreign policy agendas.

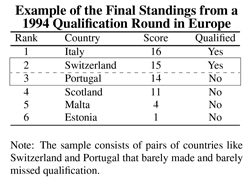

Image  |

| Image by Andrew Bertoli. (Table 2 from the paper). |

To test whether international sporting events increase state aggression, the study examines the World Cup qualification process from 1958 to 2010. Over these years, most countries had to qualify for the World Cup by playing a series of games against other states and earning a top position in the final standings. This allows one to compare those who barely qualified to those that did not. The randomness of those who qualified was essentially like a coin-toss; therefore, this approach resembles a randomized experiment. The research hones in on pairs of countries that did not have more than a two-point difference in the standings. Overall, there were 142 countries that qualified or missed the cut by two points or less. These countries were similar across political, economic and demographic factors.

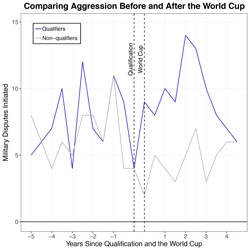

Image  |

| Image by Andrew Bertoli. (Figure 2 from the paper). |

The qualifiers and non-qualifiers also had comparable past levels of aggression, which were measured by the number of militarized interstate disputes (MIDs) that countries initiated. These disputes are occasions when countries explicitly threatened, displayed or used military force against other states. Yet, despite the two groups’ similarity on past levels of aggression, the qualifying countries started many more military disputes after they went to the World Cup. The results were driven by countries where soccer is the favorite sport. Countries such as the U.S. did not appear to experience any change in aggression from this type of nationalism.

For the pairs of countries who were opponents at the World Cup, the likelihood of aggression increased by 56 percent, as the number of pairs with at least one conflict spiked from nine before the World Cup to 14 afterward. The total number of disputes that these pairs of countries had jumped from nine to 21.

Although World Cup nationalism may serve as a catalyst for international conflict, the research points out that international sports still have the power to encourage unity, as was the case for the Ivory Coast and its participation in the 2006 World Cup.

To help prevent international sports from creating conflict, the study proposes that: rival countries or those with military disputes not play each other, countries with nationalist conflicts not be permitted to host such events and that sporting events organizers consider a new format where countries play as small regional blocks. Reforms such as these could in turn help restore some of the more aspirational notions of peace and community through international sport.

Bertoli is available for comment at: abertoli@dartmouth.edu.