This Focus on Faculty Q&A is part of a series of interviews exploring what keeps Dartmouth professors busy inside—and outside—the classroom.

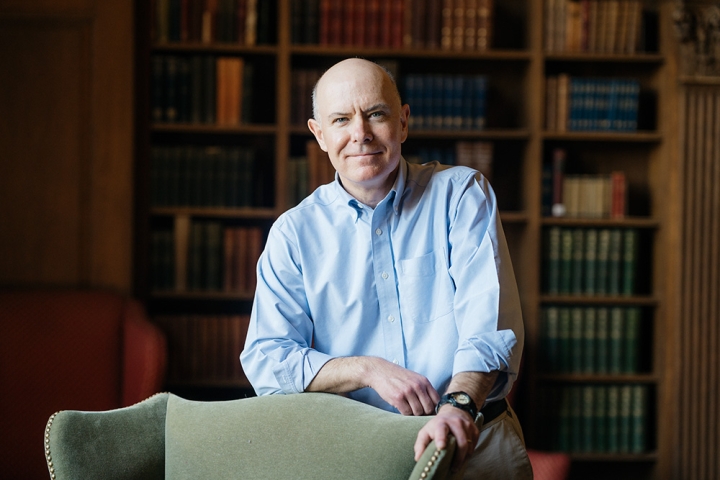

Douglas Irwin, the John French Professor of Economics, is an expert on trade. He is the author of eight books on the subject, including, most recently, Clashing Over Commerce (2017), a comprehensive history of U.S. trade policy lauded by The Economist as a “grand narrative.” His articles and commentaries have appeared in scholarly journals and in the national press, where he is often quoted. He talks with Dartmouth News about U.S. trade policy, the process of writing a book, and why he passes out four-colored pens to his students.

Imagine that President Trump calls you up and says, “Doug, you’re a terrific guy, but you’re all wrong about trade.” How would you respond?

Well, I wouldn’t be optimistic that I could change his mind. From his perspective, a trade deficit is a bad thing because it indicates a country is “losing.”

Does that frustrate you, as someone who has written about the false promise of protectionism?

There’s not necessarily anything wrong with running a trade deficit. The United States has had trade deficits since the mid-1970s—with no economic harm. Economists don’t think about international trade as win-lose or zero sum in any sense. In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith said that we shouldn’t view commerce as an adversarial relationship; it’s a cooperative relationship in which both sides benefit.

In your latest book, Clashing Over Commerce, you say that the direction of U.S. trade policy has shifted only twice in our history. Is the country undergoing another fundamental shift?

That remains to be seen, but so far it doesn’t look like it. After threatening to pull out of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement), he renegotiated it with relatively few changes to the underlying structure. The same thing happened with KORUS, the U.S.-Korea trade agreement. So there is less here than advertised.

If protectionism doesn’t protect, why do Trump and others persist in pushing a protectionist agenda?

Well, because if you’re imposing a tariff on, say, imported steel, you’re raising the price and helping the domestic steel industry and its workers. That’s a benefit to them. Trump is trying to reach out to factory workers and blue-collar workers who think that globalization has been a bad deal.

Except there are ripple effects.

Yes, the ripple effects are less apparent. One ripple effect is that steel consumers pay higher prices. Now we’re going to lose jobs in certain sectors, just as we’re gaining some in the steel industry. There’s always that trade-off.

But does any of this ultimately matter if, as you point out, there’s been remarkable economic stability over the long run, no matter what U.S. trade policy has been?

Well, my book covers about 250 years. Looking through that broad lens, there’s more stability than one might otherwise assume. In the past two years, however, there’s been remarkable instability, with a lot of rhetoric and threats and badmouthing of trade. There’s the question of whether we snap back after the Trump administration is out of office. But it’s also important to keep a historical perspective, because we’ve been through these trade spats before.

Clashing Over Commerce was published last November. Did you know how timely the book would be?

Absolutely not. I started writing articles about U.S. trade policy in the mid-1990s. I realized I had been moving forward and backward in time, covering different episodes. It made sense at some point to put it all together, fill in the gaps, and write a comprehensive history of U.S. trade policy, which hadn’t been done by an economist since the 1930s. When I finished it in September 2016, the presidential election was a month and a half away. Most everyone thought Hillary Clinton was going to win. In that case, trade policy wouldn’t have been on the front burner.

Are you itching to write the next chapter?

It’s still too soon. Much depends on whether Trump is a one- or a two-term president.

Critics have praised your clear narrative writing style. Is that something you work at?

Writing is work, so I spend a lot of time at Baker Library going over the same chapter again and again, buffing and polishing. I remember seeing my father (University of New Hampshire economics professor Manley Irwin) in the library, always rewriting, and that taught me about the process.

When you’re not teaching or writing, you’re often called on to offer expert opinion to the news media. Do you enjoy your role as a public intellectual?

My academic mentors impressed upon me the idea that our role as educators does not stop in the classroom. To the extent that I can contribute usefully to the public debate over trade, I am happy to do so. The media calls have been torrential since President Trump took office.

How do you make the dismal science less dismal for your students?

My first formal teaching position was at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, teaching prospective MBA students. They’re much less accepting than undergraduates of whatever it is you say.

Grad students kept you honest.

Exactly. Undergraduates tend to be less assertive. My experience at Chicago taught me not to waste time on arcane or overly theoretical topics that aren’t interesting or practical.

Speaking of practical, I understand you pass out embossed pens to your students.

They say, “Dartmouth Economics 39 International Trade,” my bread-and-butter course. It’s a four-color pen. Thanks to China, they’re cheap. I couldn’t afford to buy one for every member of the class if they were made in America!

Why bother?

They’re little mementos, but there’s also a practical reason. My lectures are very diagram-intensive. I do a lot of drawing with colored chalk or colored markers. So when the students are taking notes—I ban laptops—they reconstruct the diagram along with me. I hear these clicks of the pens when I’m drawing. That’s music to my ears.

What do find most remarkable about your students?

Uniformly, they’re bright, they’re engaged, they’re interesting, and they’re well-mannered in the sense that they take their responsibilities seriously. They’re just so easy to teach.

Are you using Clashing Over Commerce as a textbook?

I am not. That would be inflicting horrible pain on an undergraduate, to have an 800‑page book required within 10 weeks. I did dedicate another of my books, Free Trade Under Fire, to the students of Econ 39, because I sort of wrote it for them.

Economics is the most popular major, is it not?

It’s the biggest major. Whether it’s the most popular, that’s a different question. The quality of teaching has improved dramatically during my 21 years here, and I think that’s one reason the department has grown. It’s not just that students want to earn a good living when they graduate; they’re actually drawn to social sciences and the questions we’re asking about health economics, schooling, and other topics of day-to-day life that are important for public policy and otherwise.

In a famous episode of The Simpsons, Homer’s negotiating skills are put to the test by his daughter. “Dad, I’ll trade you this delicious doorstop for your crummy old Danish,” says Lisa. Gullible Homer agrees and turns over his pastry. Have you ever made a brilliant trade?

There is a picture of me and my sister when we were very young. She has a toy that I’m interested in, one of those snow globes, as I recall. I’m trying to get her to exchange it for something else. But I’m not sure how that worked out or who got the better end of that deal. One of the key precepts of trade, of course, is that it be voluntary.