On Sept. 22, 1918—a century before the COVID-19 pandemic—a Dartmouth freshman named Clifford Orr, Class of 1922, wrote a letter to his mother: “Spanish influenza, grippe, and pneumonia have made their appearances here. … I only hope I can steer clear of it.”

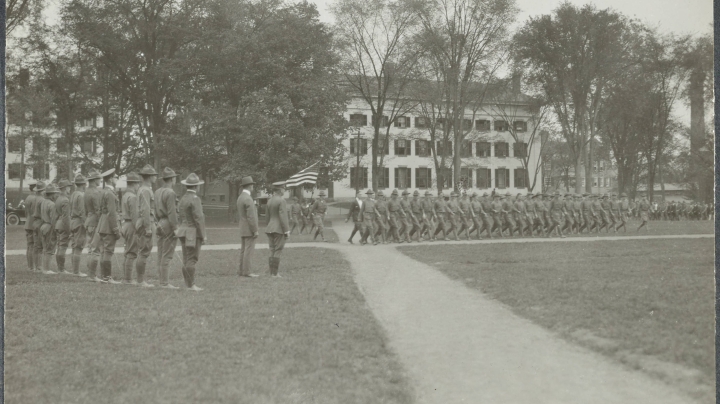

Orr did not, in fact, manage to “steer clear of” the flu—he was one of 325 members of the Dartmouth community sickened during the 1918 pandemic’s second wave that fall, which killed a professor, five students, and 10 soldiers on campus training for World War I deployments, according to a 2006 Dartmouth Medicine article chronicling Dartmouth’s response to the crisis. This toll was relatively small, considering that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates the virus killed 50 million people worldwide, including 625,000 in the U.S, in three waves between the spring of 1918 and the summer of 1919.

Letters like Orr’s, archived in Dartmouth Library’s Rauner Special Collections Library, are an invaluable resource for piecing together a picture of the everyday experience of individuals living through turbulent times, says College Archivist Peter Carini.

Documenting Troubled Times

In its 250 years, Dartmouth has seen its share of turbulence. In the 1860s, a contingent of students left Hanover before exams to join the Union cause. During World Wars I and II, much of campus life was given over to military training. In 1970, when Ohio National Guard troops opened fire on antiwar protesters at Kent State University, faculty approved President John Kemeny’s plan to suspend regular classes for a week in favor of teach-ins and gave student protestors a credit-only option for the term’s courses.

In fall 1918, Orr was lucky: His mild case of flu kept him in bed for several days on a diet of toast and milk “brought me by kind neighbors,” he wrote, but within a week he was back in class. Unlike in 2020, Dartmouth did not send students home, much less attempt to implement distance learning.

But the pandemic profoundly curtailed campus life, as Orr indicated in a letter to his father dated Sept. 27: “Chapel has been cut out, the movies closed, and Dartmouth Night, which was to be held next Monday to celebrate the College’s 150th birthday, has been cancelled.... The epidemic has killed what little college life there was.”

It’s details like these from the archival record that can help show what’s unprecedented about the current moment—and what our time may have in common with the past, Carini says.

“This is the first time I’m aware of that the College has closed to the extent that it has, and we’ve got this interconnectivity with the internet that’s different from anything we’ve ever seen before,” he says. “But some things are similar. Dartmouth is readying gymnasium space for potential overflows from the hospital; that was something that was going on in 1918. And I think the general concern for one’s own health that we’re seeing now was also similar.”

Unprecedented Interconnectivity

The interconnectivity of the current era is allowing Dartmouth’s faculty and students to adopt remote teaching and learning—supported by a backbone of critical non-teaching staff such as, among others, instructional design, education technology, accessibility services, and the libraries, including Rauner.

“There’s a whole team of us supporting faculty with remote teaching,” Carini says. “We’re identifying materials we would normally use in the classroom, scanning them, and working with faculty to rethink the class sessions that we normally do for an online environment.”

Among the challenges is conveying the material qualities of archival objects on a virtual platform, and creating opportunities for students in disparate time zones and home situations to engage with the library’s materials in as much depth as possible.

“One faculty member I’m working with has students in Europe and California, so they are only rarely going to be able to meet as an entire class,” Carini says. “So we’re rethinking how to have those students interact with the materials.”

Preserving the Human Response

In addition to addressing the current needs of faculty and students, Carini and his colleagues are already considering how to preserve the records future historians will draw on to understand the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on individuals in the Dartmouth community and beyond.

“For historians, it’s that personal piece, the individual human response, that adds depth to the official documentation,” he says.

For all our interconnectivity, Carini sees the potential for information to be lost. Applications such as Snapchat and TikTok—“tools students are using right now to communicate their thoughts, fears, amusements”—are inherently ephemeral, as are communications tools like Slack and Zoom, and even social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, unless creators save content in other formats or use web archiving tools.

“The electronic world is more transient than a lot of other communications from the past,” he says. “We have this idea that everything gets stored and saved, but it can be very hard to track. I think we’ll be missing a lot of documentation that we might have had otherwise.”

In his 16 years at Rauner, Carini has experience preserving institutional history, though nothing of the scale of the current pandemic. One example: the Occupy Dartmouth movement that began in fall 2011, inspired by larger Occupy movements around the country. Though it was quieter than movements at other colleges and universities, Carini saw the activism at Dartmouth as important to its history.

“I didn’t make a conscious attempt to document it at the time, because we don’t want to make people self-conscious about keeping things,” he says. “Part of what makes the historical record interesting is the things that do get kept. What becomes part of the archival record has to do with what seems important to the individuals who were part of those experiences—what they see as important in the scope of time.”

After the demonstrations ended, individuals volunteered documentation of the events, including a trove of emails, a collection of protest posters, and photographs and artifacts from the movement’s tent outside of Collis.

“Appropriate documentation has a way of finding its way to the archives over time,” Carini says. “Which isn’t to say I don’t stay up at night worrying that there are things we should be more consciously documenting.”

Collecting a Broad Range of Experiences

For the Dartmouth experience of COVID-19, Carini is interested in collecting stories from as diverse a sample of the community as possible.

“It’s the well-off students like Clifford Orr—much as I adore him as a past figure—whose materials tend to come to us,” he says. “But we want the broadest picture that we can get in terms of documentation. We want stories from people who might not feel that their voice is the most likely to be heard.”

For would-be record-keepers, he notes that despite all the advances of 21st-century communications technology, “Pencil and paper is a good thing. If somebody’s inspired to write on paper, we can be sure that will be around in 30, 50, maybe 150 years.”

For the latest information on Dartmouth’s response to the pandemic visit the COVID-19 website.

Hannah Silverstein can be reached at hannah.silverstein@dartmouth.edu.