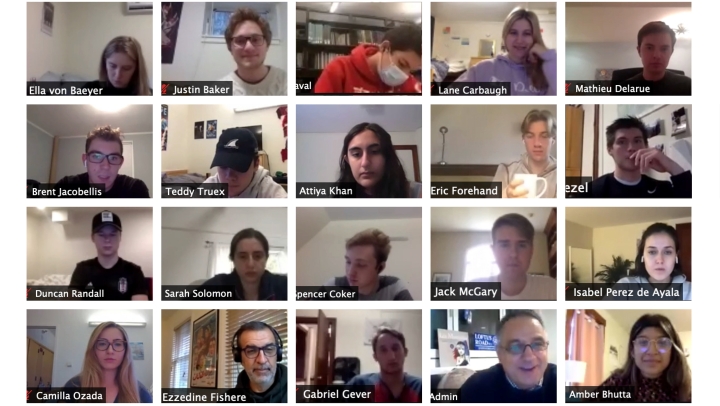

When Senior Lecturer Ezzedine Fishere realized he would be teaching his “Introduction to Middle East Politics” class remotely in the fall term, his first thought was, Zoom is annoying.

“But then I thought it is also an opportunity. I’m not teaching something that requires a lab, but we’re teaching about a distant region. The fact that, like us, people in the region are online right now creates an opportunity to transport students to the Middle East,” says Fishere, a novelist, diplomat-turned-academic, and contributing columnist at The Washington Post.

Fishere’s work has connected him with many international leaders, analysts, and activists throughout the Middle East, many of whom were happy to speak to the Zoom class with his students.

“The Middle East, like every region, has a lot of diversity, but students tend to think of it as homogenous,” he says. “We had conversations with people from all over the region. They met and interacted with people from Turkey and Egypt and Saudi Arabia and so on. When students talk with people from Iran one week and from Israel another week, it gives them different perspectives.”

Ella von Baeyer ’24 and Luca Caviezel ’24, who both took “Introduction to Middle East Politics” as one of their first classes at Dartmouth, called it a remarkable experience.

“I think the remote nature of the class actually benefited us in terms of being able to have access to some of Professor Fishere’s connections,” says Caviezel. “It was amazing to see the kind of people that Professor Fishere had come speak to us, including former members of government, leaders of think tanks, and overall experts in their fields.”

Caviezel says the class, which is cross-listed by the Department of Government and the Middle Eastern Studies Program, helped him decide to major in government.

Von Baeyer, who was drawn to Dartmouth because of the War and Peace Studies Program at the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding, says Fishere’s class gave her the access to policy leaders that she was hoping for when she came to Hanover.

“I really appreciated their insider knowledge on the Middle East, which, as we learned in class, can be a notoriously tricky region to get reliable sources out of,” von Baeyer says. “A particular favorite speaker of mine was Mozn Hassan, a feminist activist from Egypt, who spoke about sexual assault and rape within refugee camps—an environment in which I had not previously thought to consider the role that gender dynamics must play.”

Fishere says once the pandemic is over, he will continue to look for ways to integrate online interactions with leaders in the region into his in-person classes.

“I’m imagining ways that, if we can keep part of the online experience once we go back to regular teaching, I can allow students to be present and experience the things that we are discussing and teaching as they happen,” Fishere says.

When the class is talking about political parties or civil society or women’s rights advocacy, Fishere says, he is thinking of ways that his students could be present to witness networking or grassroots coalition building or conflict-resolution negotiations.

“Almost everybody has got to use online communication in ways that we didn’t before, and I don’t think this will go away,” Fishere says.

For the latest information on Dartmouth’s response to the pandemic visit the COVID-19 website.

Bill Platt can be reached at william.c.platt@dartmouth.edu.