The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted daily life, including many people’s ability to exercise, which can boost mood, reduce stress and benefit one’s physical and mental health. A Dartmouth study finds that pregnant women whose exercise routines were impacted by the pandemic have higher depression scores than those who have continued to exercise as usual. The study, whose findings are published in PLOS ONE, is among the first to examine the links between COVID-19, exercise changes and prenatal depression.

Given the physiological changes that pregnant women experience, they are at a higher risk for depression than the public. The research team set out to find out if pregnant women’s exercise routines had changed due to the pandemic, if disruptions were linked to depression and how this affect may vary between women living in metropolitan versus non-metropolitan areas.

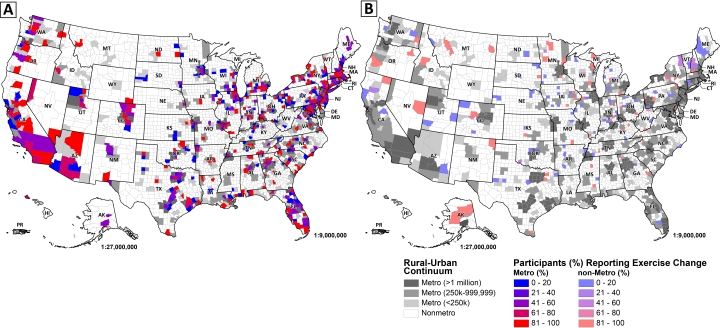

The study was based on data from the COVID-19 and Reproductive Effects (CARE) Study for which more than 1,850 pregnant women were surveyed online from April to June 2020, on how COVID-19 had affected their prenatal and post-partum well-being and healthcare. Pregnant women from all 50 U.S. states and Puerto Rico took part in the study. At the time that the survey was conducted, 92 percent of participants indicated that stay-at-home orders were in effect.

Participants were asked questions about their geographic location (i.e. where they lived, based on their zip code) and if their exercise routine had changed at all during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the number of days per week that they had engaged in moderate exercise for at least 30 minutes. They were screened for depression symptoms using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Survey (EPDS), which has long been considered the gold standard for measuring prenatal and post-partum depression. Participants were asked to respond to prompts on how they had been feeling in the past seven days, such as if they had been so unhappy that they had been crying, and to indicate the frequency in which they felt that way, ranging from “yes, most of the time” to “no, not at all.” Participant characteristics associated with depression risk and exercise patterns were also collected, including age, current gestational week, race/ethnicity, household income, education level, if financial stress had been caused by the pandemic, and whether the pregnancy was classified as high-risk. The researchers were then able to assess whether exercise routine change is associated with a depression score independent of these other important factors.

“Our results demonstrate that the COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate the elevated risk that pregnant women have for prenatal depression,” explains lead author Theresa Gildner, a research associate and the Robert A. 1925 and Catherine L. McKennan postdoctoral fellow in anthropology at Dartmouth. “Moderate exercise has been shown to decrease depression risk in pregnant women, so disruptions to exercise routines may lead to worse mental health outcomes.”

On average, study participants were 31 years old and 26 weeks pregnant. Most women were physically active: 56 percent reported that they engaged in moderate exercise at least three times a week. The average Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Survey score for participants was 10.6. EPDS depression scores can range from zero to 30, and a score of 15 or higher indicates clinically significant depression.

Forty-seven percent of the pregnant women in the study indicated that they were exercising less during the pandemic, while nine percent indicated that they were exercising more.

Pregnant women who reported changes to their exercise routines exhibited significantly higher depression scores compared to women reporting no exercise change. In addition, women living in metropolitan areas of all sizes were more likely to experience exercise changes. Pregnant women in metropolitan areas were twice as likely to say that their exercise routines had changed than women living in non-metropolitan areas. These results coincide with the COVID-19 related stay-at-home orders and the shuttering of businesses this past spring. With many fitness and recreational centers closed, and no space to work out at home, exercise routines for many pregnant women in metropolitan areas were upended. Pregnant women living in densely populated areas versus rural areas also may have been more reluctant to go outside for a walk, due to concerns of becoming infected with COVID-19.