A process that uses heat to change the arrangement of molecular rings on a chemical chain creates 3D-printable gels that can fold, roll, or just hold their shape, according to a Dartmouth study.

The researchers describe the new process as “kinetic trapping.” Molecular stoppers—or speed bumps—regulate the number of rings going onto a polymer chain and also control ring distributions. When the rings are bunched up, they store kinetic energy that can be released, much like when a compressed spring is let loose.

Researchers in the Ke Functional Materials Group use heat to change the distribution of rings and then use moisture to activate different shapes of the printed object.

The ability to print objects with different mechanical strengths using a single ink could replace the costly and time-consuming need to use multiple inks to print items with different properties.

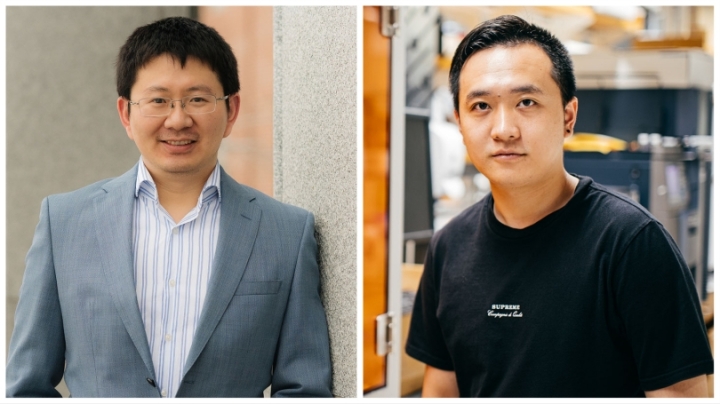

“This new method uses heat to produce and control 3D inks with varieties of properties,” says Chenfeng Ke, an assistant professor of chemistry and the senior researcher on the study. “It’s a process that could make the 3D printing of complex objects easier and less expensive.”

Most common 3D printing inks feature uniform molecular compositions that result in printed objects with a single property, such as one desired stiffness or elasticity. Printing an object with multiple properties requires the energy-intensive and time-consuming process of preparing different inks that are engineered to work together.

By introducing a molecular “speed bump,” the researchers created an ink that changes the distribution of molecular rings over time. The uneven rings also transform the material from a powder into a 3D printing gel.

“This method allowed us to use temperature to create complex shapes and make them actuate at different moisture levels,” says Qianming Lin, Guarini ’21, first author of the study.

A video demonstrating the research shows a flower printed using a 3D ink produced with the process. Different parts of the printed flower have different levels of flexibility created by the arrangement of molecular rings. The mixture of properties allows the soft petals to close when exposed to moisture while the firmer parts of the flower provide structure.

Printing the same flower using current 3D printing methods would come with the extra challenge of combining different printed materials.

“The different parts of this object come from the same printing ink,” says Ke. “They have similar chemical compositions but different numbers of molecular rings and distributions. These differences give the product drastically different mechanical strengths and cause them to respond to moisture differently.”

The study, published in Chem, accesses the energy-holding “meta-stable” states of molecular structures made of cyclodextrin and polyethylene glycol—substances commonly used as food additives and stool softeners. By installing the speed bumps on the polyethylene glycol, the 3D-printed objects become actuators that respond to moisture to change shape.

According to the research team, future efforts to refine the molecule will allow precision control of multiple meta-stable states, allowing for the printing of “fast-responsive actuators” and soft robots using sustainable energy sources, such as variation in humidity.

The resulting printed objects could be used for medical devices or in industrial processes.

Longyu Li, a former research associate, Miao Tang, Guarini ’22, Jayanta Samanta, a research associate, Lingyi Zou Guarini ’25, and Shangda Li, also contributed to this research.