Miranda Zammarelli, Guarini, was a graduate student at Dartmouth for just nine days when her interests in birds, history, and archives converged in a set of old filing cabinets in New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

She had spent the first days of June 2021 brainstorming projects with her adviser, Professor of Biological Sciences Matt Ayres, as they explored a 25-acre area within the long bowl-shaped valley of the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest that is reserved for studying birds.

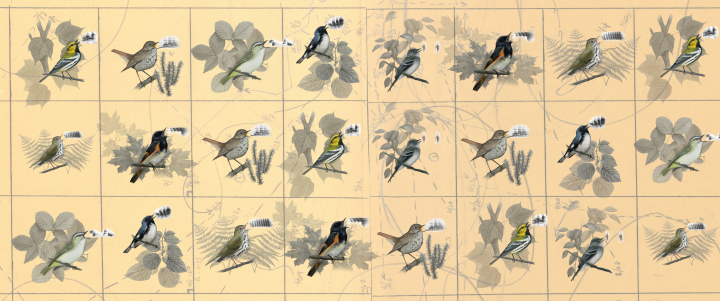

But it was in the main building at Hubbard Brook, about a 60-mile drive northeast of Hanover, that she was shown a store of hand-drawn paper maps for every year since 1969. The parchment-thin maps were the work of Richard Holmes, now an emeritus professor of biological sciences, who for more than 50 years led students into the forest for several weeks at the peak of spring breeding season to document the territorial boundaries of songbirds by listening for their distinctive songs.

“One word: Amazing,” says Zammarelli, who as an undergraduate at the University of Rochester worked as an archives clerk in its special collections library. “I love history and I love data, and I was in awe of all these data.”

Zammarelli started working with Holmes to digitize and preserve the maps, leafing through pages adorned with the dates that two generations of Dartmouth students—many of them older than her parents—used to mark when and where they heard a song.

Sometimes, when a male bird sings, a nearby male of the same species sings back, creating “territorial rap battles” that reveal who is holding what ground and where the boundaries are, Zammarelli says.

Circles on Maps

Holmes and his students created maps from those songs by layering the thin sheets over one another until they could see the locations of the territories of each species for the entire season. Circles drawn around the clusters of dates show where mated pairs of each species had staked a claim. The hand-scrawled numbers thin toward the edge of each circle, beyond which lay the border of another circle and a different pair’s turf.

“I spent two weeks digitizing maps and thinking about the questions we could answer with these data,” Zammarelli says. “It’s amazing what eight hours a day in front of a scanner will do for your thinking.”

She noticed that over 50 years, the size of the circles changed with the abundance of birds on the plot. The maps showed that territories shrank when the population was high and expanded when it was less so.

But individual species showed a stable preference for certain parts of the forest over others, with their territories clustered in specific habitats regardless of the surrounding population abundance. A few species disappeared from the study plot as the forest aged and the available habitats changed.

“We would not know what these birds’ preferences were without this data set,” Zammarelli says. “Long-term data helps us account for environmental variation over time and allows us to know if individuals have preferences for certain spaces, even as the surrounding environment changes.”

That observation resulted in a recent paper Zammarelli published in Ecology Letters with Holmes, Ayres, and other Dartmouth researchers suggesting that the multitude and ubiquity of songbird species may be related to this ability to hold defined but flexible territories that adapt to population pressure.

Zammarelli conducted spatial analysis on the digitized maps with David Lutz, an assistant professor of environmental science at Colby-Sawyer College and a visiting scholar in the Environmental Studies Program at Dartmouth, and Hannah ter Hofsted, a past Dartmouth faculty member who is now an assistant professor of integrative biology at the University of Windsor in Canada.