Lakes and other freshwater systems are getting saltier. And while de-icing salts spread on roads and sidewalks, agricultural fertilizers, mining practices, and climate change all contribute to the increasing salt pollution, current water quality guidelines do little to protect against the negative impacts, according to a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The United States and Canada are among a mere handful of countries that stipulate safe levels of salinity in their freshwater ecosystems. But the study found that aquatic life and food webs suffer damage from salt concentrations that are much lower than the thresholds their governments deem safe.

Biology professor Kathryn Cottingham and former postdoctoral fellow Jennifer Brentrup led the experiments at Dartmouth, which was among the study’s 16 sites spread across North America and Europe.

According to Cottingham, it has been apparent to researchers that conductivity rates—a measure of how much salt and other ions are in the water—have been going up since the 1990s in New Hampshire. “We knew that at some critical level, salt was going to be a problem for the organisms in the water, but we didn’t know what the threshold was,” she says. When a collaborative effort to pinpoint the threshold by leveraging an international experimental network emerged out of a scientific meeting, the Cottingham Lab readily signed up.

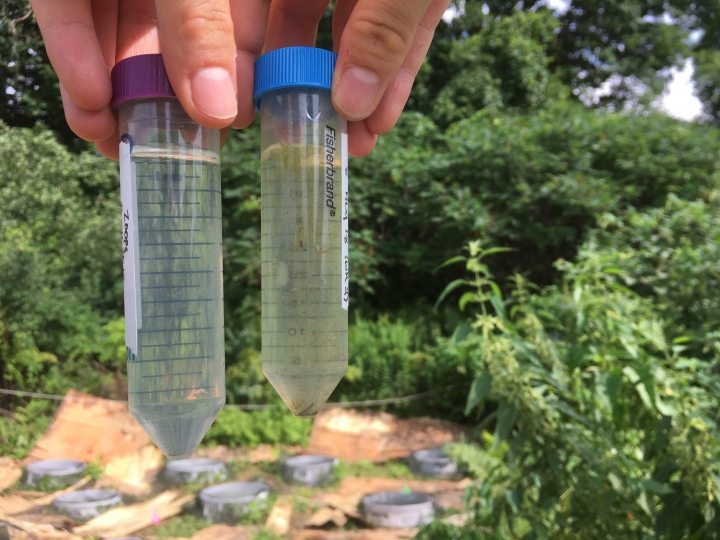

Brentrup, Alexandra Conway ’20 and two Hanover High School students collected water from four freshwater sources in the Upper Valley—Storrs Pond, Goose Pond, Mascoma Lake and Boston Lot Lake. They used the water to create “mesocosms”, which Cottingham described as “tiny, artificial ponds housed in trash cans that were buried in the ground at the Organic Farm.”

The all-woman research team created a treatment set-up in which increasing amounts of salts were added to some of the mesocosms they created. Water samples were collected weekly for six weeks and the researchers counted how many zooplankton—tiny crustaceans or other small aquatic animals—there were under a microscope.

“As the salinity increased, we saw a pretty big decline in the numbers and diversity of zooplankton that were present,” says Brentrup.

Zooplankton are key connectors of the aquatic food web, linking microscopic producers to fish. Their loss triggers cascading effects that can affect fish populations while benefiting algae at the base of the food web.

Chronic salt concentrations above 230 milligrams of chloride per liter of freshwater are considered harmful by the Environmental Protection Agency. But even at the lowest salt concentrations they tested, just 20 milligrams of chloride per liter, the researchers recorded a noticeable drop in what zooplankton species were present and how many. That’s just a teaspoon of salt in 80 gallons of water, says Brentrup. Their results corresponded with findings across the study’s sites.

“It’s clear that the salinity thresholds that have been chosen by governments as safe aren’t adequately protecting aquatic life,” says Cottingham.

Besides rethinking these guidelines at the federal level, local authorities, institutions and even individuals must be more thoughtful about how and when salt is used to keep ice from forming, she says. A host of clever solutions from pre-treatment of roads to new technologies like smart plows that aid targeted salting are now available, says Cottingham. Adopting these alternatives can help keep the roads less icy and lakes less salty.

The research at Dartmouth was funded in part by the Matariki Network of Universities, a consortium of leading international institutions of higher learning that Dartmouth co-founded.