If every cell in our bodies contains the same genetic information, why are the cells in our guts different from the cells in our muscles, which are different from the cells in our brains?

The answer has to do with how genes in each cell are regulated so that the cell develops according to the relevant genetic instructions for its function. And key to this regulation, it turns out, is microRNA—a new class of RNA molecules discovered by former Dartmouth professor and Geisel School of Medicine geneticist Victor Ambros, now the Silverman Professor of Natural Science at UMass Chan Medical School, and his colleague Gary Ruvkun, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School.

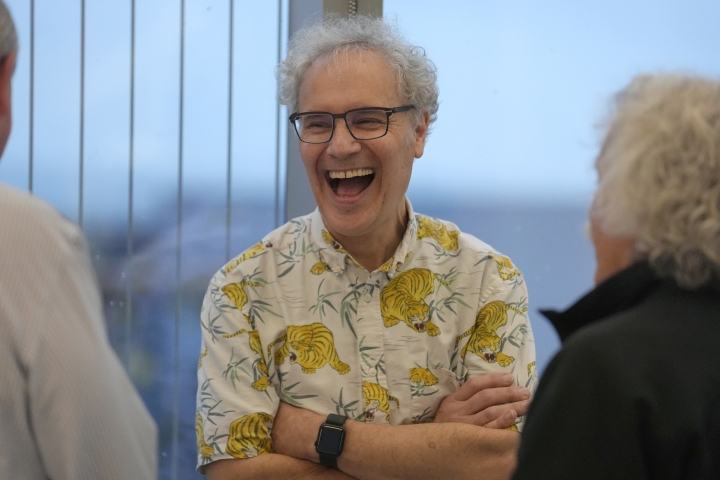

For that breakthrough, Ambros and Ruvkun are sharing the 2024 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

“Their groundbreaking discovery in the small worm C. elegans revealed a completely new principle of gene regulation. This turned out to be essential for multicellular organisms, including humans. MicroRNAs are proving to be fundamentally important for how organisms develop and function,” the announcement by the Nobel Prize website says.

Ambros described the significance and origin of his prize-winning discovery during a news conference at UMass Chan Monday morning. Early on, he and researchers in his lab noticed that a gene mutation in C. elegans would cause the organism to repeat larval cell division repeatedly and not transition to later developmental stages. It would reach adulthood missing adult parts, while having multiple juvenile features. That led him to think that “maybe there’s this clock that’s telling the animal how to develop properly.”

MicroRNA ended up being that clock, one of numerous mechanisms through which genes in our cells communicate and coordinate activity.

“What microRNAs really end up revealing for us is a way that parts of our genome can communicate with other parts of the genome and regulate the activity of those other parts in a coherent way,” Ambros said.

“Dr. Ambros and his colleagues have helped reshape our understanding of how cells develop, with profound implications for the diagnosis and treatment of everything from specific cancers to heart disease,” says President Sian Leah Beilock. “Dartmouth is proud to have been a home for Dr. Ambros’ research and teaching for many years, and on behalf of his many colleagues and friends here, I am thrilled to congratulate him on this well-deserved recognition of his life’s work.”

Ambros came to Dartmouth in 1992 as a tenure-track faculty in the College’s Department of Biological Sciences. The landmark paper announcing the first discovery of microRNAs, based on previous research done by Ambros and his colleagues during his stint at Harvard University, was published in 1993 in the journal Cell.

In 2001, Ambros became the third faculty member to join a newly created department of genetics at Geisel, “where he played an active role in teaching and mentoring junior colleagues as well as being a leader in an ever more prominent research field,” says Jay Dunlap, the Nathan Smith Professor of Molecular and Systems Biology and of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at Geisel, who chaired the Department of Genetics within Geisel when Ambros was hired.

It was during this time that Ambros, working with his spouse and longtime collaborator, Rosalind “Candy” Lee, who was a research assistant in his Geisel lab, used computational and molecular tools to reveal an abundance of microRNAs in C. elegans.

Their 2001 Science paper was among three publications that were awarded the Newcomb Cleveland Prize by the the American Association for the Advancement of Science for advancing the understanding of microRNAs and their role in gene control.

Ambros and Lee’s work helped define the criteria—size and structure—for identifying microRNAs across species, not just worms, using computational tools rather than molecular screens, says Dunlap.

“He was relentless in pursuing this interesting biology that was just a curiosity when he started. But he stuck with the problem and kept at it no matter where it led him,” Dunlap says. “So, he wasn’t limited by the tools, he simply created or learned the tools he needed to pursue the problem, and he just wasn’t deterred.”

Professor of Biological Sciences Mary Lou Guerinot recalls the department recruiting Ambros to Dartmouth in 1992.

“His lab was just across the hall from mine. I still remember celebrating the acceptance of his seminal 1993 Cell paper at a party held in the third floor hallway of the old Gilman building,” she says.

C. Robertson McClung, the current chair of the Department of Biological Sciences, says he taught genetics for several years with Ambros when he first arrived at Dartmouth.

“It was a wonderful experience. He really did an amazing job of simplifying and clarifying complex issues,” McClung says. “He was the same at the committee meetings of PhD students. He always asked the most thoughtful questions and always would provide some insight that would move things forward. His comments were always constructive.”

Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Elizabeth F. Smith, the Paul M. Dauten, Jr. Professor of Biological Sciences, also recalls friendly discussions with Ambros when she was an assistant professor and he was at the College.

“His curiosity had no boundaries. Our labs were on the same floor of the old Gilman building and sometimes he would drop in just to ask ‘what’s new’ in my research, and really listen and ask insightful questions. The breadth and depth of both his knowledge across fields and his curiosity to learn more were astounding,” Smith says.

She says Ambros was a “kind and generous” colleague, offering to take several professors who were running in the Covered Bridges Half Marathon in Vermont to the start.

“Even while waiting for the race to start, we were all talking science,” Smith says.

Ambros’ links to Dartmouth and the Upper Valley are strong. He was born at the then-Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in Hanover in 1953 and grew up as one of eight children on a dairy farm in nearby Hartland, Vt. (Ambros’ mother, Melissa, was a writer. His father, Longin, grew up in a small village in Poland, was orphaned at 8, and was in forced labor under the Nazis for five years as a teen. After a stint in the U.S. Army, he moved to the Upper Valley in the early 1950s.)

Victor Ambros graduated from Woodstock Union High School and was accepted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he majored in biology as an undergraduate and went on to complete his PhD, supervised by David Baltimore, who won the Nobel Prize in 1975 for the discovery of the enzyme known as reverse transcriptase.

As a postdoctoral fellow at MIT, he worked with another Nobel laureate, H. Robert Horvitz. Ambros taught at Harvard for eight years before joining the faculty at Dartmouth, where he taught genetics from 1992 to 2008. He joined the faculty at UMass Chan in 2008.

His professorship at UMass Chan was endowed by one of his former Dartmouth students, H. Scott Silverman ’97, and his father Jeffrey Silverman.

Scott Silverman did an honors thesis in Ambros’ lab when he was at Dartmouth.

“I was in Victor’s lab all four years that I was at Dartmouth, and it was a very close relationship, and such a special opportunity to grow close to him and his family as a student and as a colleague in the lab,” Silverman says.

“The most memorable part of my interactions with Victor was that he has this incredible, insatiable curiosity. It’s almost childlike, when he gets excited and animated about things. And it wouldn’t just be science, it could be any topic. Obviously, in particular, he gets excited about science and discovery, and he created a real passion in me for thinking about innovation.”

Another former student, Christopher Hammell, MED ’02, said Victor Ambros and Candy Lee were “his scientific parents” and ran what felt like a “family-style operation.” Hammell had Ambros on his doctoral thesis committee.

“It was so wholesome and communal that it is incredible that such profound stuff came from such a healthy environment. After being in many other scientific environments, I can’t state how unique it is now,” says Hammell, who was also a postdoc with Ambros at UMass Chan and is now a professor at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York.

“Now that I have to think about how to run an effective lab, I strive to do things like I would imagine him doing them,” Hammell says. “When presented with a scientific problem, I try to think how he would think about it by using pure logic. When it comes to giving advice to my own trainees, I literally think of him before I speak.”

Ambros, in the news conference, discussed the importance of supporting research.

“In the moment, I’m very aware that this presents an opportunity for me to speak to some of these issues that I’ve been trying to address or mention about the importance of public support of research, the importance of the best kinds of leadership and institutions, the importance of collegiality and sharing amongst scientists,” Ambros said. “All these principles that I find so important for the advancement of science and that were so important for my success and my career, I want to shout out to the world that all these things are really important.”

Ruvkun, too, has a Dartmouth connection: his daughter, Victoria, is on track to graduate as a medical student from Geisel in 2025.

To date, three Dartmouth alumni have won a total of four Nobel Prizes. They include chemist K. Barry Sharpless ’63, who pioneered the field of “click chemistry” and won the chemistry prize twice, in 2001 and 2022; geneticist George Snell, Class of 1926, who received the 1980 award in medicine for his work on immunology; and physicist Owen Chamberlain ’41, who received the physics prize in 1959 for discovering the antiproton.

At the news conference on Monday, Ambros said he was genuinely surprised to receive the Nobel. He thought his work and research related to it had been recognized when researchers Andrew Fire and Craig Mello received the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of RNA interference.

“I was astonished and surprised, delighted. Everything you might expect,” Ambros said. “Honestly, this was not something I expected. In my opinion, the Nobel Prize to Mello and Fire encompassed all these phenomena that we study. That was my sense and I was comfortable with that.”

Ambros said that the Nobel Prize and his work exemplifies that “model organisms are absolutely the drivers of new knowledge in the life sciences.”

“These kinds of studies of laboratory organisms are critical and key and fundamental to advancing understanding of biology,” he said. “And I mean advancing understanding of biology in that we are constantly moving into territory that is unexpected. The unexpectedness of biology is the most important principle, perhaps, for people to appreciate.”

Ambros’ drive and passion for his field doesn’t surprise members of his family. A brother, Theo, recalls him building his own reflecting telescopes and an observatory on the family farm, contributing data to an astronomy magazine.

Victor “was and is a farm kid from Hartland Vt.,” Theo Ambros says. “What distinguishes him is he applied his depth of curiosity with a persistence that yielded results.”