If you started watching a movie from the middle without knowing its plot, you’d likely be better at inferring what had happened earlier than predicting what will happen next, according to a new Dartmouth-led study published in Nature Communications.

Prior research has found that humans are usually equally good at guessing about the unknown past and the future. However, those studies have relied on very simple sequences of numbers, images, or shapes, rather than on more realistic scenarios.

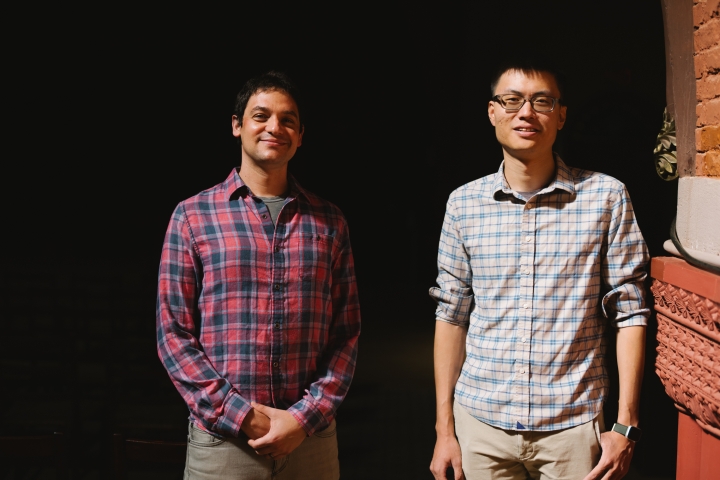

“Events in real life have complex associations relating to time that haven’t typically been captured in past work, so we wanted to explore how people make inferences in situations that are more reminiscent of everyday life,” says senior author Jeremy Manning, an associate professor of psychological and brain sciences and director of the Contextual Dynamics Lab at Dartmouth. “Real life experiences, unlike abstract sequences, often include other people.”

For the study, participants watched a series of scenes from two character-driven television dramas, Why Women Kill on CBS and The Chair on Netflix. They were asked to either guess what had happened before each scene, or what would happen next.

Participants were consistently better at guessing what had happened before a just-watched scene than they were at guessing what would happen next.

The researchers found that participants’ inferences were heavily influenced by references to specific past and future events in characters’ conversations. Like people in real life, characters in both shows often talked about their past experiences and future plans. Since the characters in those two shows tended to talk more about their pasts, participants had more clues to work from to make inferences about past rather than future events.

To determine if this pattern of talking more about the past extends to other conversations as well, the team analyzed millions of dialogues in novels, movies, television shows, and more. They found that fictional and real people alike tend to talk more about their pasts than their futures.

Even though we can make plans for the future, our memories only tell us about our past. Just as real people remember their prior experiences but not those in the future, so too do fictional characters, perhaps in an effort by writers to help them appear realistic, according to the co-authors.

“Our results show that on average, people talk one-and-half-times more about the past than the future,” says Manning. “And this seems to be a general trend in human conversation.”

Prior research has referred to the phenomenon of remembering the past but not the future as the ‘psychological arrow of time.’

“This phenomenon also reflects that one knows more about their past than their future,” explains lead author Xinming Xu, Guarini, a PhD student in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences and member of the Contextual Dynamics Lab. “Our study shows that a person’s asymmetric knowledge of their own life can be transmitted to others.”

Ziyan Zhu at Peking University and Xueyao Zheng at Beijing Normal University also contributed to the study.