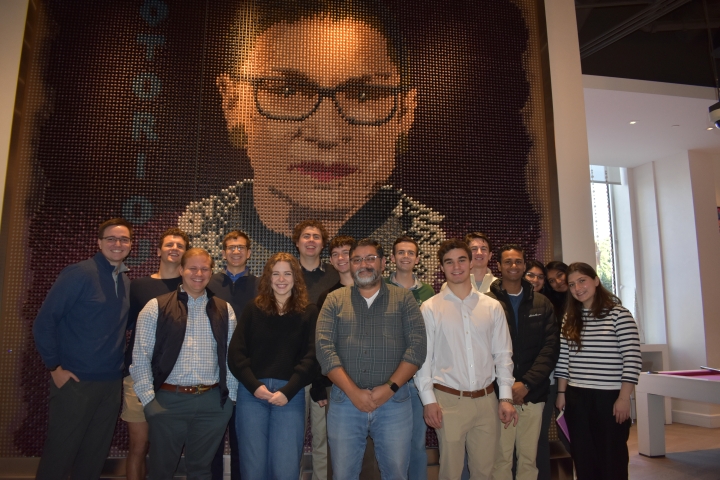

Students in Econ 70: Frauds, Panics, Crashes, and Bank Runs, spent a week in New York and a week in Washington this winterim meeting with top regulators, financial policy leaders, and institutional investors.

That included people with vivid experiences of financial meltdowns, such as former Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner ’83, who guided the economic recovery efforts following the global financial crisis of 2008.

Professor Bruce Sacerdote’s ’90 fall term class led students in the study of historic shocks to the financial system including the Silicon Valley Bank run, the COVID-19 recession, the 2000 internet stock market bubble, the 1998 Russia crash, the hyping of crypto, and other market disruptions going all the way back to the Great Depression.

“And of course, most famously, we have the 2008 financial crisis. Virtually everyone that we’ve seen was not only alive during that period, but was very active in either making laws around it, passing emergency provisions, or in trying to guide a financial institution through those provisions and invest in those conditions,” Sacerdote says.

In addition to Geithner, who is now president of the private equity firm Warburg Pincus in New York, Sacerdote’s 16 students met earlier this month with experts including:

- David Erikson ’92 at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; where he works on the Community Reinvestment Act, which encourages banks to expand access to credit in low- and moderate-income communities;

- Aaron Klein ’98, of the Brookings Institution and the former deputy assistant secretary of the treasury and chief economist for the Senate Banking Committee who drafted the 2010 Dodd Frank Act and the federal Troubled Asset Relief Program to stabilize the financial system after the 2008 financial crisis;

- and Mark Calabria, currently at the D.C.-based Cato Institute, who was director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency and who wrote the law for the conservatorship of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, government sponsored corporations that facilitate a secondary market for mortgage-backed securities.

Francina Kolluri ’25 says meeting with more than a dozen high-level regulators and market experts was a remarkable opportunity, and it made her realize how complex and vital it is to respond effectively to disruptions to the economy.

“I think it’s easy to be engulfed in the theory and things that you read in books and all of the research and literature that’s coming out, but seeing that in practice with how our regulators take it, how they’re able to implement that in their work every day, has been really exciting,” Kolluri says.

It helped her understand that no two market crises are the same and that a response can only be made after broad debate among players with a wide range of viewpoints.

“These frauds, these panics and crashes are not things that can be remedied in the system by one person. It’s a collective range of thought and effort that’s really going to get us there,” Kolluri says.

“For example, with the 2008 crisis, Mark Calabria thought that there was too much fiscal policy. And then Aaron Klein thought that there was too little, and that they should have done more in the beginning to help out low-income households specifically, and try to balance that sense of equity in the system,” she says.

Nathan Shibley ’25 says a key takeaway for him was how passionate the leaders were about the impact of their work and their sense that a collaborative effort among people with diverse views is the way to find solutions.

“The idea that you can’t outregulate or outlegislate fraud and abuse was surprising to me,” he says. “These were people who were speaking from years of experience at the Securities and Exchange Commission, for example. It was interesting to see the humility that regulators have to have in terms of understanding that people will always skirt around regulation.”

And the respect these leaders of finance have for colleagues who hold different positions, and their willingness to share their experiences with students was inspiring, Shibley says.

“I’m realizing that some of the most successful and interesting people are also very generous with their time,” he says. “Maybe that is partly a function of the Dartmouth connection.”

Sacerdote says students were able to ask the people they met with how they found their passion and what they studied at Dartmouth.

“We got a lot of good career advice from alumni about being open minded and letting their passions and intellectual interests pull them into interesting jobs,” Sacerdote says.

Funding for the Econ 70 immersion experience is provided in part by the Political Economy Project.